Raqqa in the Shadow of ISIS: Conflict and Civil Resistance

Introduction

In 2011, a revolution erupted against Syria’s Assad regime. Over the next months and years, as peaceful protests were violently suppressed, the revolution steadily militarized. By 2013, anti-Assad militias were operating throughout the country. These exceptional security conditions led to changes in the roles, forms, and goals of civil activity within society.

Free Syrian Army and Jihadist militias took full control of Raqqa in March, 2013, dramatically altering the Syrian military landscape. While the militias attempted to assert their authority over the inhabitants of the city by force, the civil revolutionary movement opposed their violent practices in various ways. Demonstrations and protests were held outside the bases and prisons run by the militias. Meanwhile, another type of conflict arose, as two local councils competed to control the city administration. This power struggle continued until

The militias seized many public buildings and converted some of them into prisons. The most prominent prisons at that time were the Raqqa governorate building prison, run by Jabhat al-Nusra; the Sharia Committee prison at the Municipal Stadium, run by various Jihadist factions; the prison at the former air force intelligence building, run by Ahrar al-Sham; and the Point 11 prison at the traffic department, run by ISIS.

These prisons terrified the population. They devoured many civilian activists, some of whom are still missing today. As a result, many civilians, including most of those involved in civil activity, gradually left Raqqa.

ISIS seized full control of Raqqa on January 13, 2014, and imposed totalitarian rule, formally ending all civil activism, whether by individuals or organizations. It also eliminated the other militias in the city. Although the change was bloody, it was not very surprising. Before taking full control, ISIS had worked alongside the other Jihadist militias in the Sharia Committee to kidnap, imprison, torture, and disappear both civilian activists and the fighters affiliated with non-Jihadist militias.

This investigation focuses on the nature of civil activism and resistance in Raqqa in this period, juxtaposing it with what was happening in the bases and prisons of the Jihadist militias. It also examines the power struggle between the competing local councils in Raqqa, a rivalry reflective of the general instability prevailing at the time.

The investigation is based on analysis of a large collection of ISIS documents scanned and kept in the IPM archive; analysis of social media footage and other open source content; and the testimonies of ten activists, former workers in the Local Council of Raqqa, and relevant military personnel. These witnesses were interviewed in 2024. Some gave permission for their names to be published, while others preferred to remain anonymous. The interviews are held in the archive of the ISIS Prisons Museum.

The text begins with a brief overview of the socio-political situation in Raqqa during the first two years of the Syrian Revolution. It then examines the military landscape, listing the main militias of the time, including ISIS, and describing their roles, the conflicts between them, their theft of public assets, and the violations they committed against the community.

After that, the investigation presents exclusive data concerning individuals kidnapped by ISIS in 2013, as well as a series of archived videos of protests by civilian activists against the violations committed by ISIS and other militias. The investigation also presents a table of prominent civil organizations and provides details of the attempts to protect public finances from the militias. Then it explores the two local councils of Raqqa, the causes of their dispute, and their respective fates.

The final part focuses on the period when ISIS was in full control. It highlights the Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently (ar-raqqa tudhba bisamt) platform, which was one of the main voices of opposition to the ISIS reign of terror.

From the Assad Regime to Militia Rule: The Transformation of the Revolution

The people of Raqqa joined the anti-Assad protest movement in its early days, calling for freedom and an end to the dictatorship that had controlled political and public life in Syria for over 40 years.

The first protest in Raqqa was held on March 25, 2011, called the Friday of Integrity (Jumat al-Izza). It championed the cause of freedom and dignity, and condemned the repressive practices of the Assad regime’s intelligence services and armed forces.

Small protests continued for months. As in other Syrian cities and towns, most protests in Raqqa started out from mosques, either after evening prayers or at noon after the congregational Friday prayer. Civil groups were active in writing pro-revolutionary graffiti on the city walls, and coordination committees were formed to unite civil activities and to organize the protests.

The scope of activity of these groups was limited during the first year of the revolution by the regime’s policy of mass arrests, detention and torture. Nevertheless, the protest movement gathered pace. The funeral of Ali al-Babinsi, who had been killed[1] during a protest by students on the first anniversary of the revolution, March 15, 2012 was attended by many hundreds, and turned into a mass protest. Once again the security forces opened fire, killing 14 people. The pace of arrests caused a lull in the popular protests in the following months. They were revitalized in 2013, but by then they were directed against other parties.

So long as the Assad regime continued to rule Raqqa, its security departments were spread throughout the city, and they controlled the population with an iron fist.

| Branch/Department | Location | Authority |

| Political Security Directorate | The Hisham bin Abdul Malek neighborhood, near the old bridge | The Political Security Directorate of Damascus |

| General Intelligence Directorate | The Nahda neighborhood | The General Intelligence Directorate of Damascus |

| Military Intelligence Department | The Nahda neighborhood | The Military Intelligence Directorate of Deir ez-Zor |

| Air Force Intelligence Department | Adnan al-Maliki Street, known locally as the Mujamma al-Hukoumi Street, near the Rashid Park | The Air Force Intelligence Directorate of the Eastern Region |

| Military Police | The Naim intersection | The Military Police of Damascus |

| Army conscription center | The Tashih neighborhood | |

| Military Housing (al-masaken al-askariyya) | The Furat neighborhood |

Table 1: The Assad regime’s security branches in Raqqa before 2013

The Military Landscape in Raqqa in 2012 and 2013

Early Militarization and Militia Formation

Various militias gained ground in Raqqa’s countryside in 2012. Some were affiliated with the Free Syrian Army (FSA), which had been founded in June 2011 by defectors from the Syrian army. Others emerged from a Jihadist background, most notably Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham.

The Hudhaifa bin al-Yaman militia was one of the first. Founded in June 2012, this Islamist-leaning militia was established with financial and military support from the Kuwaiti Ummah Party, as well as from the Syrian rebel alliance called Jabhat al-Asala wa al-Tanmiya (the Authenticity and Development Front), according to author and researcher Mabad al-Hassoun. Many violations against the people of Raqqa were attributed to this militia.

In the following months, a group of militias were formed under the banner of the FSA. They included Shuhada al-Raqqa, founded on July 17, 2012. Then on August 8, 2012, a group of 11 individuals bearing light arms announced the formation of the Naser Salah al-Din militia. Mabad al-Hassoun was a secret participant in the formation of this group.

In September 2012, after a three-day battle, a joint force of FSA-affiliated militias and Jabhat al-Nusra defeated Assad regime troops near the Tell Abyad border crossing with Turkey. This was part of the larger Border Crossings Battle. On September 20, the rebels captured Tell Abyad town. Assad’s troops consequently redeployed, withdrawing from the Raqqa countryside and relocating to the security branches in Raqqa city; the military and security bases in Tabqa, near the province’s strategic dams and oil fields; and the headquarters of the 17th Division.[2]

Soon afterwards, on September 27, 2012, Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa was formed. This militia would later participate in the battle to capture Raqqa city. It declared its allegiance to the Military Revolutionary Council in Raqqa, a body which also included the following militias: al-Jihad fi Sabil Allah, Sawaiq al-Rahman, al-Naser Salah al-Din, al-Haq, Shuhada al-Raqqa, Saraya al-Furat, Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan, and Ahrar al-Furat. Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa was led by Ahmad Alloush, also known as Abu Issa,[3] who had participated in the revolutionary movement and as a result had been arrested twice in the early days of the Syrian Revolution.[4]

On December 25, 2012, Jabhat Tahrir al-Raqqa (the Raqqa Liberation Front) was formed. This was an umbrella group bringing together the main FSA militias in the province. According to the video declaration, these militias were: Liwa Rayat al-Nasr, Kataeb al-Farouq, Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul, Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa, Liwa Isar al-Shamal, Hudhaifa bin al-Yaman, Liwa al-Muntaser Billah, Liwa Sheikh al-Islam, Liwa al-Rasafa, and Liwa Fursan al-Furat. In the same video, the new group declared the start of the battle to liberate Raqqa.

By then, Jabhat al-Nusra was already well established. Since early 2012, it had spread across the areas of Syria that had slipped the Assad regime’s control. Some of Nusra’s units took up positions in the Raqqa countryside. In the same period, Ahrar al-Sham – another militia with a Jihadist background – established a significant presence in the countrysides of Aleppo and Idlib.

The Militias in Raqqa

By early 2013, the Assad forces had withdrawn from Raqqa’s countryside and relocated to central Raqqa, the 17th Division headquarters, and its bases in Tabqa. This led the militias of the FSA, Ahrar al-Sham, al-Jabha al-Islamiyya al-Souriyya (the Syrian Islamic Front), Kataeb al-Farouq, and Jabhat al-Nusra to besiege the Assadist positions. The militias captured these positions one by one, starting with the Baath Dam on February 4, 2013. Next they captured Tabqa and the Furat Dam on February 11, then the Raqqa Central Prison on March 3, and Raqqa city center, the Political Security Branch, the General Intelligence Branch, the Air Force Intelligence Branch, the Governorate Building, and the Baath Party Branch on March 4. Finally, on March 7, they captured the Military Intelligence Branch.[5] However, they were unable to capture the headquarters of either the 93rd Brigade[6] or the 17th Division[7].

With the Assad regime expelled from the city, the atmosphere in Raqqa now changed completely. The main military actors were the two largest Jihadist militias, Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra. Within a few weeks, the smaller Islamist militias merged into these dominant groups. The main FSA-affiliated non-Islamist groups were Jabhat al-Wahda wa al-Tahrir, Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa, and Kataeb al-Farouq.

The following table shows the main militias in Raqqa in 2013:

| Name of militia | Subsidiary militias | Creation Date | Main Figures |

| Jabhat al-Nusra | Abu Saad al-Hadrami | ||

| Ahrar al-Sham – Eastern Region | Muhammad al-Omar Abu Omar | ||

| Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa | Al-Jihad fi Sabil Allah

Sawaiq al-Rahman Al-Naser Salah al-Din Al-Haq Shuhada al-Raqqa Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan Saraya al-Furat Ahrar al-Furat Suqour al-Jazira Usoud al-Tawhid |

2012/09/27 | Ahmad al-Alloush (Abu Issa) |

| Hudhaifa bin al-Yaman | Ahl al-Athar

Hizb Allah Usoud al-Sunna Saraya Aal al-Bayt |

||

| Al-Failaq al-Thani | Isar al-Shamal

Al-Izza Lillah Sheikh al-Islam Ibn Taimiya Liwa al-Ansar Liwa Ghuraba al-Islam Al-Murabetoun Abayi bin Kaab Abi Zarr al-Ghafari Suqour Quraish Saif al-Rasoul Al-Saliheen |

2013/04/15 | Bashar Tlas |

| Division 11 (Al-Firqa 11) – Free Syrian Army | Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa

Liwa al-Muntaser Billah Liwa Umanaa al-Raqqa Liwa al-Naser Salah al-Din in Raqqa |

2013/07/17 | |

| Liwa al-Naser Salah al-Din al-Ayyoubi | 2012/08/08 | ||

| Liwa al-Jihad fi Sabil Allah | 2012/03/04 | Farha al-Askar – Abu Wael | |

| Liwa Oweis al-Qarni | Rayat al-Haq

Saraya al-Sunna Ahfad Hamza Osama bin Zaid Abu Bakr al-Siddiq Salman al-Farsi Jund al-Sharia Al-Defa al-Jawwi |

2013/04/13 | Abdul Fattah al-Naser – Abu Muhammad |

| Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul | Anwar al-Haq

Aisha Um al-Moumenin 101 Abu Bakr al-Siddiq Ahrar al-Jazira Saraya al-Furat Bayt al-Maqdes wa Jund Allah Al-Maham al-Khassa |

2012/10/20 | Abdullah Othman Abu Mazen al-Sakhni Abdullah Dib Ujail Abdul Karim al-Ujail – Abu al-Zain |

| Liwa Umanaa al-Raqqa | 2012/09/01 | Qasem al-Bals Abu Abdullah, Fadel Oweid al-Sweidan (Abu Fahd), sheikh Khalil al-Ibrahim | |

| Liwa al-Muntaser Billah | 2012/12/11 | Captain Abu al-Laith Captain Abu Suleiman |

|

| Liwa Isar al-Shamal | 2012/11/17 | Major Bashar Tlas | |

| Jabhat Tahrir al-Raqqa | Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa

Liwa al-Qassam Liwa Rayat al-Nasr Kataeb al-Farouq Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul Hudhaifa bin al-Yaman Isar al-Shamal Liwa al-Muntaser Billah Liwa Sheikh al-Islam Al-Rasafa Liwa Fursan al-Furat |

2012/12/25 | |

| Jabhat al-Wahda wa al-Tahrir al-Islamiyya fi al-Raqqa | 2012/06/01 | Samer Ma’youf al-Mteiran Adana Subhi al-Ersan |

Table 2: The major militias in Raqqa in 2013[8]

The militias raced to seize governmental institutions and buildings. All the witnesses interviewed for this investigation say that the furniture, vehicles, and other assets of most government institutions were taken by the militias as soon as they had ejected the government employees. The following table – based on cross-referencing information provided by witnesses – lists the government buildings commandeered by the militias.

| Government Institution | Militia / Violation |

| Central Bank | Ahrar al-Sham is accused of stealing the deposits |

| General Electricity Corporation | Commandeered by Ahrar al-Sham |

| School Books Press | Commandeered by Ahrar al-Sham |

| Scientific Research Center (al-buhouth al-ilmiyya) | All the vehicles and other assets were stolen. |

| Faculty of Sciences | The contents were stolen by a leader of the al-Muntaser Billah militia |

| Train Station | Used as a base by Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul |

| Governorate Building | Used as a base by Jabhat al-Nusra, then ISIS |

| Diyafa Palace | Used as a base by Hudhaifa bin al-Yaman |

| Municipal Stadium | Used to house the Sharia Committee |

| Military Justice building | Commandeered by Ahrar al-Sham |

| Oweis al-Qarni shrine | Used as a base by Jabhat al-Nusra |

Table 3: Militia seizures of government buildings and public assets

During the early months of the militias’ control, and before ISIS declared its existence, Ahrar al-Sham was the dominant force in Raqqa. It exerted control by managing public resources and assuming responsibility for some public services. It also pushed for the formation of the Sharia Committee, which consisted of representatives from various militias. The Sharia Committee hoped to assume many governmental functions. According to author Abdul Qadir Laila, some of these had been previously performed by the interior ministry or the municipalities, while others were similar to the functions performed by military courts.

The Sharia Committee was headed by Yaser Aouf, an Islamist dentist who had formerly been a prisoner in the Assad regime’s Saydnaya Prison. Some describe him as a unity figure who was not partial to any specific group, while others believe he was backed by Jabhat al-Nusra.

In order to placate the local tribes, Ismail al-Lajji, a local man and a member of the al-Muntaser Billah militia, was appointed as the committee’s vice president. He was backed by Ahrar al-Sham. The makeup of the committee leadership indicates that Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham were effectively in control, while the other militias played a minor role.

The Sharia Committee used the Municipal Stadium as its headquarters, and established a temporary prison there. Khudr al-Sheikh, who was a Raqqa local council member at the time, describes the role of the Sharia Committee as “poor”, saying that it mixed up “legal, administrative, and sharia matters.” He adds that militias sometimes adjudicated cases themselves without referring them to the Sharia Committee. Abdul Qadir Laila says that the committee relied heavily on military force, which enabled it to hold the smaller militias to account.

Although witness testimonies indicate that the Sharia Committee played a limited role in the city, and that the detention facility it operated was small, and more of a temporary holding center than a major prison, the IPM has documented violations by the committee against civil activists. These included Remal Noufal, who was detained and beaten in the committee’s prison.

In a September 2013 interview,[9] Remal explains that she was selling coffee mugs adorned with the Syrian Revolution flag at Rashid Park in central Raqqa when a group of armed, masked men from the Sharia Committee appeared and asked her to leave. She was selling the mugs as part of a fundraising campaign, and was accompanied by a male colleague who was documenting the campaign. Remal and her colleague refused to comply with the masked men’s request. The men left, but returned after half an hour and arrested Remal’s colleague. Remal then confronted them, saying, “Your Sharia Committee does not represent me.” Now accompanied by five other activists, Remal went to the Sharia Committee in the Municipal Stadium and demanded the release of her colleague. Remal recounts meeting a sharia judge at the committee who accused her, amongst other things, of “taking the Muslims’ money” and “fundraising for the Free Syrian Army.”

Remal returned the next day to again request the release of her colleague. This led to an argument with the sharia judge, which resulted in her arrest. She was arrested by a female jailer called Um Hamza. At this point Remal shouted, “Don’t believe that members of this Sharia Committee fear God!” During her detention, Um Hamza insulted her and beat her with an electric cable. She was later released after mediation by people close to her family.

The Sharia Committee Prison was not the only prison run by the militias. Dozens of city residents were detained or disappeared at these sites.

| Prison | Militia | Location |

| Sharia Council Prison | Ahrar al-Sham, Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS | Municipal Stadium |

| Governorate Building Prison | Jabhat al-Nusra, then ISIS | Governorate Building |

| Point 11 Prison | ISIS | Traffic Building |

| Air Force Prison | Ahrar al-Sham | Air Force Intelligence Building |

Table 4: The main militia-run prisons in Raqqa in 2013

ISIS to the Forefront

May 3, 2013 was a critical date. A group of fighters in Raqqa announced that they had abandoned Jabhat al-Nusra, and that they pledged allegiance instead to the Islamic State in Iraq and Sham (ISIS), which had been declared the previous month by its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. This led to a split in Jabhat al-Nusra. The Nusra commander in Raqqa, Abu Saad al-Hadrami, left the city with a group of fighters and headed to Tabqa. However, the majority of Nusra fighters joined ISIS. The organization now appointed Ali Mousa al-Shawwakh, also known as Abu Luqman[10], as its emir in Raqqa.[11] Abu Luqman would later play a key role in the ISIS security system.

ISIS made clear its aim to crush the rival militias. In the summer of 2013, it clashed with Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul,[12] capturing its base at the train station after detonating a car bomb which caused civilian casualties.[13] After that, ISIS targeted the smaller militias either in battle or by kidnappings and assassinations. Abu Yazan, the leader of Liwa al-Naser Salah al-Din, and Abu Taif, the leader of Liwa Umanaa al-Raqqa, were among those assassinated.[14]

| Date | Event | Location |

| 03-08-2013 | Fighters of Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul opened fire at an ISIS car at a checkpoint | Maarri School checkpoint |

| 08-08-2013 | Clashes between Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul and ISIS | Around the train station |

| 13-08-2013 | ISIS detonated a car bomb at the Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul base | The train station neighborhood |

| 14-08-2013 | Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul attacked ISIS checkpoints. Four of the Liwa’s fighters were killed in the attack. | Raqqa |

| 18-08-2013 | Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul announced a cessation of attacks against ISIS “to preserve unity and eliminate division.” | Raqqa |

| 13-09-2013 | ISIS arrested nine fighters from Liwa Ahrar Souria, who had come to Raqqa to search for their kidnapped leader Ali Balou. | Raqqa |

| 21-09-2013 | ISIS members raided the base of al-Katiba al-Tayyiba militia at the Radio and Television Building. | Raqqa |

| 01-10-2013 | High tension between Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS in Raqqa caused by ISIS arresting a Nusra commander and fighters. | Raqqa |

| 17-11-2013 | ISIS kidnapped Abu Raad al-Weisat, a commander of Liwa Oweis al-Qarni. | Raqqa |

| 24-11-2013 | Clashes between ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra at the Nusra base in the Governorate Building. ISIS captured the base and a number of Nusra fighters. | The Governorate Building |

| 07-12-2013 | Clashes between Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS after an ISIS member was shot dead when he failed to stop at a Nusra checkpoint. | Raqqa |

| 30-12-2013 | Fighters from Jabhat al-Nusra ejected ISIS members who had tried to assault employees of the Raqqa Local Council. | Raqqa |

| 04-01-2014 | All opposition and Jihadist militias were on high alert after Ahrar al-Sham detained two ISIS members who had attempted to attack the Security Office with hand grenades. Jabhat al-Nusra fighters closed off the road to the Governorate Building, which was now an ISIS base. A military column from al-Jabha al-Islamiyya (the Islamic Front) moved through the streets. | Raqqa |

Table 5: Timeline of the major clashes between ISIS and its rivals in Raqqa in 2013 and early 2014[15]

Hundreds of Forced Disappearances

The infighting between the militias in Raqqa motivated activists to protest against the militias in general and the Jihadist ones in particular, especially ISIS. ISIS responded with intensified intimidatory violence. The forced disappearances of civil society figures were a key part of its effort.

The following table shows some of those abducted in Raqqa in 2013.[16]

| Name | Date of Birth | Occupation | Date of Abduction | Place of Abduction | Abducting Party |

| Omar Abdul Qader al-Ali | 1990 | Salesman | 10-03-2013 | opposite the Firdaous Pharmacy, Firdaous neighborhood | Jabhat al-Nusra |

| Mahmoud Ahmad al-Anizan | Free Syrian Army fighter | 15-03-2013 | Raqqa | Jabhat al-Nusra | |

| Naser Ahmad al-Ali | 1972 | Driver | 04-05-2013 | In front of his house | Jabhat al-Nusra |

| Abdullah Muhammad al-Khalil | 1961 | Lawyer | 18-05-2013 | In front of the military court | ISIS |

| Al-Muntaser Abdullah al-Khudr | Council Member (Assad regime) | Raqqa Province | 2013 | ISIS | |

| Al-Haitham al-Haj Saleh | 1967 | Teacher | 21-05-2013 | At his house next to the Murouriyya Park, Raqqa | ISIS |

| Yaser Ali al-Jasem | 1985 | Merchant | 25-05-2013 | The medical clinic opposite the Engineers Association | ISIS |

| Ramadan Sadeq al-Ramadan | 26-05-2013 | ISIS | |||

| Muhammad Ali al-Nuweiran | 10-06-2013 | ISIS | |||

| Hussein Hassan al-Suweilem | 1980 | Tailor (women’s clothes) | 01-07-2013 | Near al-Dabba shops on Saif al-Dowla Street | ISIS |

| Fawwaz Hijab al-Bathawi | 1983 | Government employee | 05-07-2013 | At the al-Riyadiyyin al-Ahrar militia base in the Municipal Stadium | ISIS |

| Firas al-Haj Saleh | Activist | 20-07-2013 | ISIS | ||

| Ibrahim al-Ghazi | Civilian activist | 22-07-2023 | ISIS | ||

| Paolo Dall’Oglio | 1954 | Priest | 29-07-2013 | Raqqa | ISIS |

| Bassam Mahmoud al-Harir | 1979 | Driver | 29-07-2013 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Mousa Ibrahim al-Zaiter | 1978 | Government employee | 01-08-2013 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Hassan Shirkuh Hassan | 1980 | Driver | 06-08-2013 | Raqqa | ISIS |

| Muhammad Nour Matar | 1993 | Photographer | 13-08-2013 | Train Station | ISIS |

| Diya al-Din Mousa al-Hamoud | 1985 | Free Syrian Army fighter | 18-08-2013 | Raqqa governorate building | ISIS |

| Khalil Ibrahim Habash | 28-08-2013 | ISIS | |||

| Abdul Latif Khalaf bin Sultan | 28-08-2013 | ISIS | |||

| Khaled Khalaf al-Mahmoud | 10-09-2013 | ISIS | |||

| Muhammad Ibrahim al-Jasem | 1965 | Government employee | 22-09-2013 | Sina’a, Raqqa | ISIS |

| Luay Ali al-Akrab | 1988 | Student | 23-09-2013 | At his family home, next to the Faculty of Letters | Ahrar al-Sham |

| Muddather al-Hassan | Free Syrian Army fighter | 03-10-2013 | ISIS | ||

| Abdullah al-Assaf Abu Abdul Rahman | 16-10-2013 | ISIS | |||

| Abdullah Dhiyab al-Assaf | 1968 | Craftsman | 17-10-2013 | The Shuaib alleyway, north of Uhud Mosque | Unknown |

| Abdul Ilah Ahmad al-Hussein | 1994 | Law student | 18-10-2013 | In front of a church in Raqqa | ISIS |

| Ismail Ahmad al-Haj Abdullah | 1978 | Farmer | 25-10-2013 | In front of the Maarri School | ISIS |

| Ismail al-Hamed | 1964 | Doctor | 02-11-2013 | ISIS | |

| Khalil Ahmad Bouzan | 1986 | Owner of the Dar al-Jami’bookshop | 05-11-2013 | Kahraba Street, Raqqa | ISIS |

| Muhammad Hamou Bakou | 1971 | Photographer | 10-11-2013 | Raqqa | ISIS |

| Ashraf Kajl bin Sheikh Muhammad | 1991 | Free Syrian Army fighter | 20-11-2013 | Raqqa | ISIS |

Table 6: Names of people disappeared by ISIS in Raqqa in 2013

The table shows that Jabhat al-Nusra perpetrated three documented abductions in the period before Baghdadi announced the merger of al-Nusra and ‘the Islamic State’. ISIS was responsible for the large majority of abductions after May 2013, however.

One of the first civil society figures to be abducted was lawyer Abdullah al-Khalil, who was the leader of the Raqqa Local Council at the time. Al-Khalil had previously been arrested multiple times by the Assad regime because he had defended political prisoners. Khudr al-Sheikh, who was al-Khalil’s deputy at the Raqqa Local Council, narrates the details of the abduction. Al-Khalil and four other men were in a car which was stopped by a group of armed men. These fighters forced al-Khalil’s companions out of the car before taking al-Khalil away. His fate remains unknown.

Al-Sheikh believes that the gunmen who abducted al-Khalil were affiliated with ISIS. He suggests several motivations for the abduction. One is a personal grudge. Another is that ISIS considered the leadership of the National Coalition, which formed the Raqqa Local Council, to be “apostates”. A third is that al-Khalil’s activism and good reputation upset ISIS, as “they [ISIS] did not want someone with such attributes, neither with them nor against them.”

The data shows that the rate of abductions increased after May – that is, after the declaration of ‘the Islamic state’.

Many civil activists were abducted in the summer of 2013, including Firas al-Haj Saleh, who had been active in the protest movement against the Assad regime, and had been arrested twice by the regime. He participated in the protests against ISIS too. This is what led to his abduction.[17]

In late July 2013, the Italian priest Paolo Dall’Oglio arrived in Raqqa. Dall’Oglio had lived in Syria for decades. He spoke excellent Syrian Arabic, and was a popular figure amongst Syrians. In 1992 he reestablished the sixth century Deir Mar Mousa al-Habashi monastery, and he worked to encourage dialogue and cooperation between Syria’s faith communities. In 2012 he was exiled from Syria by the Assad regime after he had criticized the regime’s violence and called for a peaceful transition of power. But after a year outside the country, he returned, first to territory controlled by opposition factions, and then to Raqqa under ISIS control. According to Human Rights Watch, he had come to negotiate the release of civil activists. Dall’Oglio entered the Raqqa Governorate Building, which ISIS had taken as a base. It seems that he never came out of the building. His fate remains unknown.

ISIS continued to disappear people who participated in protests against it, as well as citizen journalists and photographers. One such was the photographer Muhammad Nour Matar. Matar was first arrested by ISIS in July 2013, then released. A month later, he disappeared again after covering the ISIS attack on the base of Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul. He has not been heard of since.

The law student and photographer Abdul Ilah al-Hussein was kidnapped after participating in protests. Another protester who fell foul of ISIS was Muhammad al-Khatib, who was detained for 48 days in the Governorate Building Prison. Despite his young age – he was only 17 at the time – Muhammad had been very active in the revolutionary movement, participating in dozens of protests. He also joined the sit-ins in front of the Governorate Building.[18]

Al-Khatib was arrested on January 20, 2013. He reports that he was beaten for an hour upon his arrival at the Governorate Building Prison, and then was put in solitary confinement. After that, he was interrogated and tortured. He was suspended from the ceiling by his hands, and endured various types of beating. He says the Governorate Building contained an execution room, and that he personally was threatened with execution there. None of the documents retrieved by the IPM, however, indicate that any of the disappeared were actually executed at that site.

Al-Khatib was later transferred to the Markabat Prison. Early in 2014, he managed to escape as battles were fought between ISIS and its rivals.

Muhammad al-Khatib and other prisoners freed from the Markabat Prison

An analysis of the available data concerning those abducted in 2013 shows that ISIS did not differentiate based on age or profession. The youngest person kidnapped was 19 and the oldest was 59. Those kidnapped came from varying professional and educational backgrounds. The common link was that they had all participated in anti-ISIS activities.

Rebellion at the Prison Gates

Immediately after the liberation of Raqqa from the Assad regime, the victorious militias began violating the rights of the city’s inhabitants. As the oppression increased, so did the popular protests. According to three activists who took part, the FSA militias responded to protestors’ demands more flexibly than the Jihadist militias. Those protests were related to specific violations committed by FSA fighters, and the dialogue between protestors and militias was based on the values of ‘revolution and freedom’.

The behavior of the Jihadist militias was quite different. One activist (who does not wish to be named) says that on several occasions the Jihadist militia Ahrar al-Sham responded violently to the protests held in front of its headquarters. On one occasion, Ahrar al-Sham fighters beat a young man who had painted the revolutionary flag on a city wall, breaking his hand. In another incident, Ahrar al-Sham fighters scared off protestors with heavy machine guns mounted on pick-ups.

The Sharia Committee set up by Jihadist militias and based at the Municipal Stadium committed many violations. Activists protested in front of the stadium to pressure the Committee into releasing those it had detained. The same anonymous activist reports that the committee once arrested two women for not wearing hijab. On that occasion, dozens of residents protested in front of the stadium until the women were released.

In the period before the emergence of ISIS, the protests were mainly held in front of the militias’ bases, especially those of Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra, and were responses to the militias appropriating public property or detaining activists.

Protest in front of an Ahrar al-Sham base near Nour Street in Raqqa, June 2013

Plea by the mother of a person detained by Jabhat al-Nusra during a protest in front of the Governorate Building in Raqqa, May 2013.

Condolences to the Homeland (Aza Watan)

On May 3, 2013, the same day that Jabhat al-Nusra fighters in Raqqa declared allegiance to ISIS, three military officers serving the Assad regime were executed in central Raqqa’s Sa’a Square. Activists from the Haqquna Movement were moved to protest the way the officers had been killed by erecting a ‘Condolences to the Homeland’ (aza watan) tent.[19]

One of the activists behind the initiative (who prefers not to be named) reports that, “ISIS said that the officers killed were from the Alawi sect, to avoid a popular rebellion. We in the Haqquna Movement considered that act [the execution] to be a violation. Even if they were officers with the Assad regime, they should have been put on trial, and not killed in such a manner. This was a violation against us and against human rights.” He adds, “We did not really know whether they were officers or not. There was confusion about that. We went to the place [of execution] and set up a condolence tent. We considered it condolences to the homeland, because their methods were killing the homeland and its spaces for freedom. It was terrorism. They were terrorizing the city. At that point, we realized we were in a fierce battle.”

The activist believes that the Condolences to the Homeland tent was a spark that ignited further acts of resistance against ISIS.

From the Condolences to the Homeland (aza watan) tent, May 2013 (YouTube)

Governorate Building Protests Break the Wall of Fear

The Governorate Building, which served as a base first for Jabhat al-Nusra and then for ISIS, became a focal point of the protests, especially after the increase of abductions by ISIS.

According to some witness testimonies, several activists and FSA fighters were detained at the site. Other testimonies indicate that ISIS transferred detainees temporarily held in the Governorate Building to secret prisons located elsewhere in Raqqa.

One witness who participated in the protests at the time says that condemnations and chants were at first aimed at Jabhat al-Nusra, as the civil movement was not always able to distinguish between Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS. Most of the protests demanded fair trials, information on the fate of detainees, and an end to human rights violations.

An early protest against ISIS – in June 2013 – heading towards the governor’s mansion.

During the summer of 2013, ISIS kidnapped dozens more civilian activists. As a result, protests were held in front of the Governorate Building almost every day. The protesters carried signs bearing the names of those abducted and slogans calling for their release.

Protest against ISIS in front of the Governorate Building after the arrest of Firas al-Haj Saleh, July 2013.

There was significant participation by women in the protests. In particular, the activist Suad Noufal played a prominent role. Noufal had participated in founding the Raqqa Local Council after the liberation of the city. As ISIS gained ground, she launched a series of solitary protests. She stood outside the organization’s bases every day for over two months, holding up handwritten signs demanding the release of prisoners and an end to violations. To start with, Noufal managed to reason with some ISIS members who had previously been her students. This disturbed the older and foreign ISIS commanders. Noufal later received death threats, and was even shot at in the street. In the end she fled Raqqa, first to Turkey, then to another country.[20]

Falak al-Hassan, who was the director of the women’s office at the Raqqa Local Council at the time, also participated in protests following the detention and disappearance of her son. Al-Hassan participated in a sit-in in front of the Governorate Building that lasted 15 days. During the first week, wives, sisters, and mothers of the abducted and disappeared attended the sit-in. During the second week, the Haqquna Movement joined in too. After that, ISIS demanded an end to the sit-in. According to al-Hassan, “When we asked them about the fate of our sons, they said they would be put on trial because they were disbelievers and heretics.” She adds that the sit-in finally ended when ISIS opened fire on it.

The IPM archive includes dozens of videos that document the protests in front of the Governorate Building throughout the summer of 2013. Women can be seen participating in most of the videos.

The human rights and feminist activist Mona Freij, who played a significant role in Raqqa’s civil movement at the time, regularly participated in these protests. She says, “In September [2013] we held a sit-in. Members of Kataeb al-Farouq (an FSA militia) had been arrested, so we went out and protested in front of the [ISIS] base. I shouted at them that they were not Muslims, that they were tarnishing Islam, and that they were treating civilians just as the Assad regime had.”

Protests in Central Raqqa

Protests against ISIS and the other militias were held at several other locations in central Raqqa, including 23 Shubat Street, Tell Abyad Street, and the Rashid Park area. Protesters chanted for the release of detainees and in support of the FSA.

Protest against ISIS at 23 Shubat Street in central Raqqa, July 2013.

Demonstration in support of the FSA and against ISIS in central Raqqa, July 2013.

Protest against ISIS in central Raqqa, July 2013.

Ramadan 2013 and the Clash of Jihadists

Civil activists held protests every evening throughout Ramadan of 2013, which that year fell in July and August.[21] They raised slogans against the Jihadist militias, such as “Ahrar al-Sham are Assad’s guys,” “The Sharia Committee [is like Assad’s] Air Force Intelligence,” and “Raqqa is Free, ISIS Out.”

On the other hand, small demonstrations raised slogans in support of the Jihadist militias, and rejected the protest movement.

This reflected a split in the community. One side supported Jihadist ideas and the Islamification of the state, while the other side called for secularism, freedom, and commitment to the original goals of the revolution.

Videos of the demonstrations in support of the Jihadists, copies of which are kept in the IPM archive, show that participation was low and limited to young men. According to witness testimonies, the Jihadist militias themselves were behind these demonstrations.

Protest against ISIS in front of the Rashid Park that resulted in skirmishes with pro-ISIS demonstrators, July 2013.

As the protests continued throughout Ramadan, a group of activists with Islamist leanings issued a declaration titled the Discord Statement. This called for an end to the protests against the militias so that all efforts could be focused on fighting the Assad regime. The statement was later retracted after a great deal of criticism was directed at the signatories.

One activist says that some Islamist youth active on the civil scene at the time were in fact supportive of the resistance against ISIS.[22] They refused to work with ISIS, abided by the principles of the civil revolution, and at a later stage engaged in discussions with the secular movement outside Raqqa to overcome points of difference.

Candlelit Vigil

In August 2013, ISIS arrested dozens of activists, photographers, and journalists in Raqqa. Civil society responded by creating new forms of opposition.

One evening that month, young men and women gathered under the new bridge in Raqqa to float lit candles down the Euphrates. The action aimed to draw attention to the oppression in Raqqa, and in particular to the arrests of civilians.

Candlelit vigil on the bank of the Euphrates at the new bridge area demanding the release of detainees from ISIS prisons, August 2013.

Attempts to Protect Public Property

Civil activism in Raqqa was manifested in various forms: individual, organized, and institutionalized. It started well before militias took control of the city with the work of local youth and student coordination committees, most of which launched revolutionary or humanitarian initiatives.

More than 40 civil society initiatives were established in the first months after the liberation of the city. Many of these were focused on service-related work. Activists interviewed for this investigation described the city in those days as a “workshop” and a “hive of activity.”

| Organization/Group/Initiative Name | Date of Establishment | Type of Activity |

| Raqqa Coordination Committee | 2011 | Revolutionary Coordination/Media |

| Raqqa Spring Movement | 2012 | Political/Service |

| Sons of Rashid Assembly | 2012 | Humanitarian |

| I’m Revolutionary | Apr 17, 2012 | Media |

| Muslim Youth Organization | Nov 29, 2012 | Missionary |

| Demos | Jan 01, 2013 | Women’s Affairs/Training/Advocacy/Rights |

| Raqqa Sharia Committee | Mar 04, 2013 | Governance/Judiciary |

| Free Raqqa Youth Assembly | Mar 17, 2013 | Civil/Voluntary/Service |

| Revolutionary Security in Raqqa | Mar 17, 2013 | Governance/Local Police |

| Haqquna Movement | Mar 28, 2013 | Rights/Political |

| Manazel Magazine | May 01, 2013 | Media |

| Raqqa Media Center (RMC) | May 18, 2013 | Media |

| Raqqa Revolutionaries Media Committee | May 18, 2013 | Media |

| Union of Kurdish Youth in Raqqa (HCKR) | May 31, 2013 | Social/Political |

| Sons of Raqqa Humanitarian Society | Jun 19, 2013 | Humanitarian |

| Ramadan Charity Project | Jun 30, 2013 | Humanitarian |

| Noor Ala Noor Charity Society | Sep 16, 2013 | Humanitarian |

| Qandaris Newspaper | Dec 04, 2013 | Media |

| Ahl al-Athar Charity Society | Humanitarian | |

| Jannah Women’s Organization | 2013 | Cultural/Women and Children’s Support/Humanitarian |

| Rawafid Organization | Humanitarian |

Table 7: Notable Civil Society Groups, Organizations, and Initiatives in Raqqa 2011 – 2013

On March 15, 2013, the second anniversary of the revolution, a group of young people publicly announced the formation of the Free Raqqa Assembly. The group had already been operating in secret before the city’s liberation, and quickly became active in filling the gap left by the shutdown of state institutions.

The Assembly launched several initiatives, including “Our Streets Breathe Freedom”, which aimed to decorate streets with revolutionary flags and slogans, and the “Clean the National Hospital” campaign, which focused on rehabilitating and reopening the hospital to patients. They also initiated the “Our Bread” and “A Child’s Right to Life” campaigns, and took part in the “Freemen Behind Bars” campaign.[23]

The Assembly brought together revolutionary activists from different backgrounds, both secular and Islamic. According to a published interview with one of the Assembly’s board members, the organization’s objectives extended beyond providing services. They aimed to act as a watchdog over the militias, applying pressure to “keep them from straying from the revolution.” The Assembly also advocated for women’s rights, and defended freedom of expression.[24]

Two civil activists interviewed by the IPM pointed to early signs of societal division over the role of the militias. While some members of the Assembly leaned toward supporting the Jihadist factions, others sought to engage in critical dialogue with them in order to challenge their violations.

Mona Freij, now a member of the Syrian Women’s Political Movement, was in charge of humanitarian aid in the city at the time. She served in the Higher Relief Committee, which was affiliated with the local council formed in Tell Abyad. For a period, this council was responsible for the whole of Raqqa province, including Raqqa city. In an interview with the IPM, Freij describes several activities undertaken by the council in collaboration with other organizations and associations. These included the For You initiative’s exhibition in early June 2013, which aimed to raise donations for orphans and impoverished families.

Freij describes the exhibition as “one of the most beautiful events that took place during that period. All the groups participated—including Haqquna, Raqqa Volunteer Team, Raqqa Civil Team, and the Civil Assembly—as well as women’s initiatives and representatives from various sectors. Even the Local Council supported the initiative. The exhibition raised enough money to buy milk for children for six months, and it was distributed to all the children in need from the General Relief Warehouse of Raqqa Province.”

But such self-organized activism was beset by difficulties. It soon became clear to those involved that welfare activities were inextricable from resistance to the military forces on the ground. The overlap arose from the fact that many of the militias were accused of seizing control of government buildings and looting public funds.

The museum, the electricity company, and the school textbook printing house were among the facilities that civil activists in Raqqa found it necessary to protect.

Mona Freij describes the latter: “Before the revolution, the Assad government imported three schoolbook printing presses, one of which was located in Raqqa’s schoolbook printing house. It was one of the finest presses. Unfortunately, we heard that members of a militia had entered the printing house and dismantled it. We gathered there, and tried to prevent them, but sadly, the sound of their weapons was always louder than our voices.”

Freij also recalls an incident at a scientific facility: “Once we stood and protested for an entire day in front of the Research Center to prevent the sale of its highly advanced machines. According to the agricultural engineers who studied there, students of agricultural engineering and agricultural development, and the agricultural institute itself, used to conduct their research at this very advanced center.” Despite the activists’ efforts, militiamen ultimately took control of, and looted, the facility.

According to five different testimonies, Ahrar al-Sham stormed Raqqa’s central bank and seized the funds within. The militia is also accused of confiscating a significant amount of public property from government offices, claiming these assets were the “spoils of war.” In addition, Ahrar al-Sham appropriated the Raqqa Museum. It claimed it was concerned with protecting the museum’s artifacts from looting. Nevertheless, the museum ultimately lost thousands of artifacts.

Khidr al-Sheikh, a former chairperson of the Raqqa Local Council, says that none of the factions provided any services to the people. Instead, he says, “They fought over ten bags of wheat and a transformer located in one corner of the city.” He recounts an incident when some of the militias took over Raqqa’s electricity directorate. “When the council was formed, our headquarters were in the electricity directorate, which contained two huge modern buildings. After the building we were using was bombed, we moved into the other one. Two months later, members of the Free Syrian Army came and demanded that we leave. Then they returned with rifles, and forced us out.”

The Local Council’s headquarters was transferred to yet another location, which was also bombed. When Khidr al-Sheikh arrived to inspect the damage, a group affiliated with the Free Syrian Army had already entered the site. “We saw them carrying away our employees’ computers,” he says. After a confrontation, the group departed, leaving the computers behind.

Al-Sheikh also recalls members of the Muntasir Billah faction looting the laboratories of the al-Furat University Faculty of Science. He approached the militia leader at the request of the faculty dean. This man refused to cooperate, treating al-Sheikh in a “humiliating” manner.

Newspapers and Social Media Pages

From the start of the Syrian Revolution, social media played a pivotal role in organizing, documenting and publicizing civil protest and activism. Later, social media platforms helped document the violations committed against the civil revolutionaries. The Raqqa Youth Coordination Committee emerged in this context in 2011, and continues to operate today.[25]

In 2013, the Coordination Committee’s social media account reported on service-related issues and military operations, focusing in particular on the abductions and other violations carried out by ISIS. The account was inactive from 2014, but resumed its coverage in 2016, once again reporting on the situation in the city.

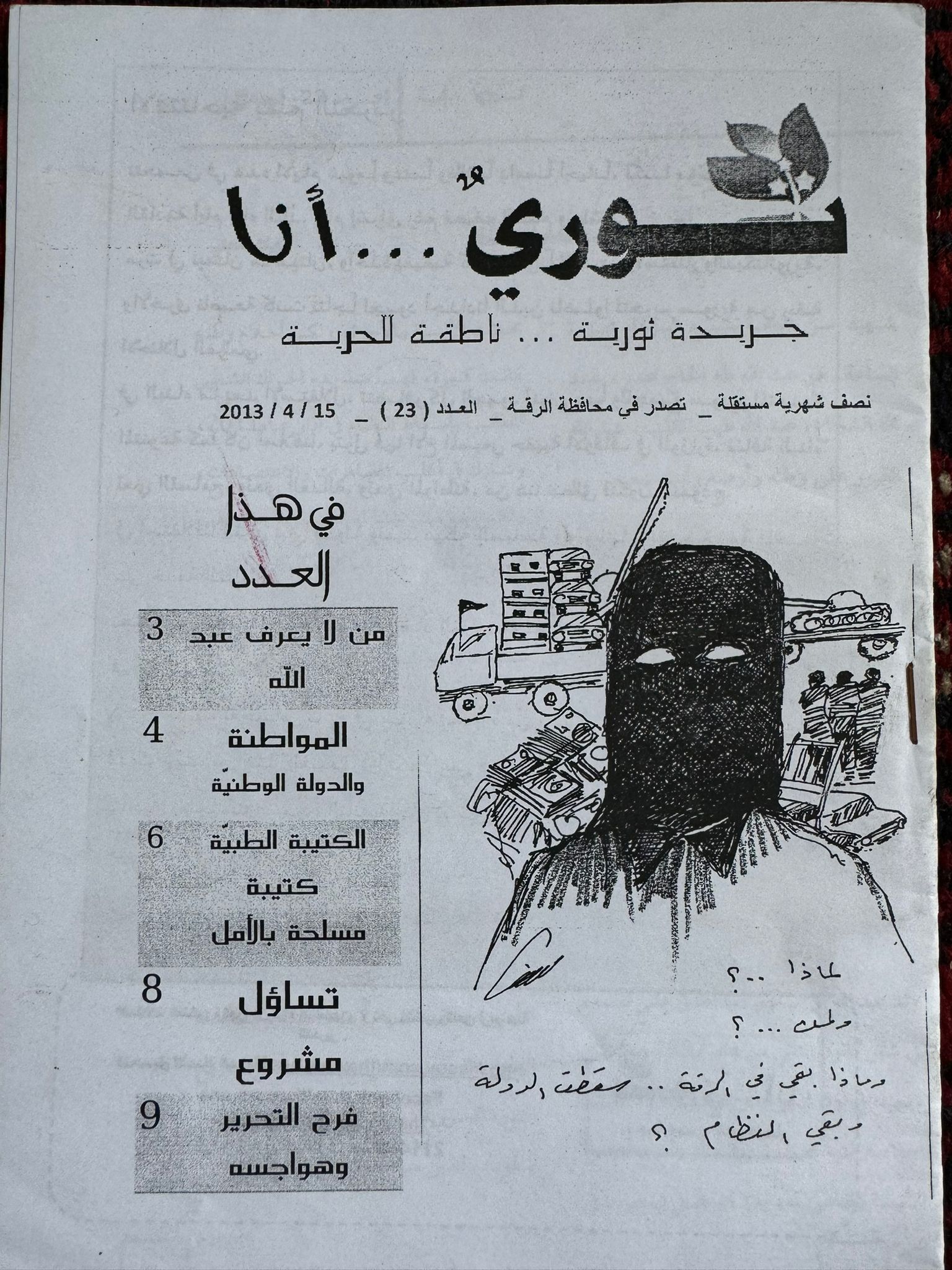

The newspaper “I’m Revolutionary” was established in 2012, describing itself as a “revolutionary newspaper, speaking for freedom.” At the time, it criticized the Assad regime, publishing caricatures, poems, personal narratives, and educational pieces. The following year, it shifted its focus to the new reality after the militias had seized control. Several other revolutionary print publications were founded during this period, including “Qandaris”, and “Kalima Hurra” (Free Word).

Cover of Issue 23 of the newspaper “I Am Revolutionary” published in Raqqa, dated April 15, 2013 (IPM Archive)

The IPM archive preserves copies of Kalima Hurra, including its fourth issue, published in April 2013. The cover describes the newspaper as “Political, Social, and Critical,” while an article titled “Did You Come as Liberators or Invaders?” criticizes the theft of goods from the School of Industry and the Scientific Research Center, describing such incidents as “the looting of Raqqa.” Another article reports public opinion concerning the declaration of the “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria,” and points out that the people of Syria were not consulted on the matter. The newspaper adopted an Islamic tone, and at the same time criticized the Islamist and Jihadist militias for their arrests of activists. It also criticized the Raqqa Local Council.

Issue 4 of Kalima Hurra (Free Word), dated April 17, 2013 (ISIS Prisons Museum Archive)

![]()

Qandaris, which began printing in May 2013, featured cultural and poetic content reflecting upon life in Raqqa. Its Facebook page, meanwhile, posted updates about the city. On August 22, 2013, the page posted a document confirming that Qandaris had received a six-month journalism license from the Local Council. This, however, was its final post.

Two Local Councils

In 2012, the externally-based National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces was working to establish local councils in the Syrian provinces. In December of that year, from the city of Urfa, southern Turkey, it announced the formation of the Raqqa Local Council. The lawyer Abdullah al-Khalil was appointed leader, and he presented a list of 60 names to form a consultative body to represent the province.

However, activists in Tell Abyad – a Syrian town on the Turkish border already liberated from the regime – had set up a temporary provincial local council. This council was headed by Saad al-Shweish. A council for the administration of the Raqqa city had also been established; it was led by Nabil al-Fawaz.

A dispute emerged over the rightful leadership of the province. Supporters of the Tell Abyad council argued that it had popular legitimacy because it had been established by consultation with representatives of communities throughout Raqqa Province; while those supporting the council led by Abdullah al-Khalil felt it should lead because it had been formed by the Coalition, and as such it was part of the broader Local Administration Councils Unit network.

The Tell Abyad council consisted of about 25 people whose names had been put forward in a special meeting. Some representatives from Raqqa city had attended the meeting. Mona Freij was one of the candidates for election to the Tell Abyad council. She explained the formation process: “We went to Tell Abyad where the elections were held, and I was the only woman there from Raqqa province. There were four candidates [from the city], so we went and the elections took place.”

After opposition factions had gained full control of the province, including Raqqa city, the council set up by the Coalition was the one that ultimately took charge. At that point it introduced a new election mechanism, which was largely based on consensus.

One of the major criticisms of the latter council was that its consultative list was compiled in secret, sometimes without the knowledge of those whose names were included. According to a civil activist of the period, several people on the list were unaware of their inclusion and had not endorsed Abdullah al-Khalil’s leadership. This was not a significant concern for everybody, however. Khidr al-Sheikh, the former director of religious endowments in Raqqa, who would later succeed Abdullah al-Khalil as the council leader, confirmed to the IPM that he understood the security justification behind the inclusion of his name on the list without his knowledge. Afterwards he worked for the council in secret, participating in distributing aid and funds sent by the Coalition. “Even though the regime still controlled Raqqa at the time,” he says, “aid still reached us. We sometimes assigned individuals to distribute it through various centers in the city, including a well-known charity licensed by the regime called The Charity and Social Services Association.”

| Council Formed by the Coalition in Urfa | Council Formed in Tell Abyad | |

| Date of Formation: | December 2012 | November 2012 |

| Chairperson: | Abdullah al-Khalil | Saad al-Shweish |

| Notable Members: | Ahmad Shalash, Usayd al-Mousa, Ibrahim Muslim | Nabil al-Fawaz, Adeeb al-Shahada, Mona Freij, Akram Dada, Saleh al-Hindawi |

Table 8: The Two Raqqa Provincial Councils at their Foundation

The Tell Abyad council was not very effective, as it had been established only as a temporary body. Though it based its legitimacy on consultation with the community, the fact that its formative meeting was not publicly announced meant that large segments of the community were unable to participate. It didn’t receive Coalition funds, but was supported financially by private interests. Khidr al-Sheikh believes that Saad al-Shweish maintained the Tell Abyad council simply to “preserve his own leadership position.”

The friction between the councils continued until March 2013, when the militias took over Raqqa. The repression of civil activists by Jihadist factions overshadowed the previous rivalry. In early April 2013, therefore, a settlement was mediated by activist groups to dissolve both the Tell Abyad council led by Saad al-Shweish and the city council led by Nabil al-Fawaz. Abdullah al-Khalil remained as the chair of the Coalition-backed provincial council. A council of elders was formed too. This body led the consultations to appoint an electorate that would vote for city and provincial council members in the future.

Abdullah al-Khalil continued to lead the council until May, when he was abducted and disappeared. Khidr al-Sheikh, his deputy, explains the council’s structure: “We formed about 16 sub-councils under the umbrella of the provincial council. There were councils for the Tell Abyad area, Suluk town, Ayn Issa town, the Tabqa region, Dibsi Afnan on Raqqa’s outskirts near Aleppo, Tell Jaber, Mansoura, a region called al-Suwaidiya, Salhabiya, al-Karama, Maadan, Sabkha, and a council for the city. Funds were distributed based on the size of the population.”

But the mechanism for distributing funds was more complex than that. Khidr al-Sheikh explains that, “meetings were held between the head of the sub-council, representatives of the council, and the provincial council chair. They would decide based on various factors, including population [size] and urgent needs. Priority was given to emergency expenditures. Everything was documented.”

The Raqqa city council was headed by lawyer Taha al-Taha. It included eight offices, including the education office, the media office, the project office, the finance office, the health office, and the women’s office. According to an interview with Falak al-Hassan, head of the women’s office at the time, the council performed many services, including cleaning public spaces and reopening schools. She says that in those early days, the militias allowed some space for discussion with council members, as they wanted public services to be restored.

Nevertheless, the security threats posed by the militias, and particularly the tightening grip of ISIS, remained the most significant challenges faced by the provincial and city councils. The clampdown continued in the months following the abduction of Abdullah al-Khalil. Khidr al-Sheikh, who now became the provincial council leader, recounts being abducted and robbed while returning from a meeting with the Coalition in Turkey. “There were three of us, including the accountant, when we were stopped by a military checkpoint, undoubtedly belonging to ISIS. They threw us into the wilderness after confiscating our bags, passports, and IDs. They took $30,000 from the accountant.”

Alongside these security issues, disputes between the provincial and city councils persisted until September 2013, when new elections were held to select members for the city and sub-councils. In any case, the city council did not last much longer. When ISIS seized full control at the beginning of 2014, most city council members fled.

Absolute ISIS Rule

Many civil and political activists had already left in the second half of 2013, as ISIS grew stronger and the security situation deteriorated. One such story of departure is told by media activist Mezar Matar, who fled after receiving threats from ISIS in October 2013. Similarly, Khidr al-Sheikh recounts that he was on a business trip to Turkey when clashes between ISIS and the rival factions flared in early 2014. After receiving warnings, he never returned to the city.

On January 6, 2014, an attack against ISIS was launched jointly by Ahrar al-Sham, the FSA-linked Raqqa Revolutionaries Brigade, and fighters still loyal to Jabhat al-Nusra. In the initial stages of the assault, ISIS fighters retreated, and were besieged in the Governorate Building. The factions managed to free dozens of those detained inside the building before the battle shifted in ISIS’s favor.[26]

Disagreements between Ahrar al-Sham, Jabhat al-Nusra, and the FSA factions facilitated the ISIS victory. By January 13, 2014, the entire city of Raqqa was under ISIS control. It remained under the organization’s rule until 2017.

The following table highlights key moments in the military clashes during ISIS’s attempt to seize control of the city:

| Date | Event |

| Jan 6, 2014 | Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, and other factions began a battleunder the name “Fakk al-Aani min Sujoun al-Jani” (Freeing the Prisoners from the Prisons of the Oppressor), aiming to release over 100 fighters from ISIS prisons. |

| Jan 7, 2014 | Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham and FSA factions clashed with ISIS. |

| Jan 8, 2014 | The clashes continued, with the fighting fiercest in the Bayatra neighborhood, around Rashid Park, the Sharia Council office, and the Political Security branch. Jabhat al-Nusra seized control of the Political Security branch and the Euphrates Basin Directorate building. |

| Jan 9, 2014 | Clashes raged on 23 February Street and Tell Abyad Street. ISIS gained control of the Owais al-Qarni shrine and the museum. The rival factions regained control of the Water Facility. |

| Jan 10, 2014 | The clashes continued. Abu Bakr al-Furati, ISIS’s military operations leader in Raqqa, was killed along with 25 fighters at the Mashlab checkpoint. ISIS captured and executed four Jabhat al-Nusra fighters. |

| Jan 11, 2014 | ISIS seized the border crossing at Tell Abyad after clashes with Ahrar al-Sham, and blew up several houses belonging to fighters of the Sheikh al-Islam Brigade. |

| Jan 12, 2014 | ISIS sent a car bomb to the Uwais al-Qarni shrine, which was being used as a base by the Thuwar al-Raqqa brigade, but it was detonated by an RPG before reaching the target. Sixty-two bodies of Jabhat al-Nusra and Islamic Front fighters were found at the National Hospital in Raqqa. They had been killed in clashes over the previous days. |

| Jan 13, 2014 | Further clashes broke out in Raqqa. The Raqqa Revolutionaries Brigade seized the electricity directorate building, while ISIS shelled the Ramila neighborhood with tank rounds. |

| Jan 14, 2014 | Clashes continued in Raqqa between the Raqqa Revolutionaries Brigade and ISIS. |

Table 9: Key moments in the military confrontations during ISIS’s attempt to take control of Raqqa.

The Fate of Raqqa’s Factions

| Faction Name | Fate |

| Raqqa Liberation Front | After ISIS took control of Raqqa, the Front moved to the Ayn al-Arab area. Later it fought against ISIS in the Raqqa and Aleppo countryside alongside the People’s Protection Units (YPG). |

| Raqqa Revolutionaries Brigade | Initially part of the Raqqa Liberation Front, the brigade moved to the northern countryside after the fall of Raqqa. It later joined the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) under the name “Raqqa Revolutionaries Front.” |

| Hudhayfah Ibn al-Yaman Battalion | This battalion joined the Raqqa Liberation Front in late 2013. Some of its members were accused of siding with ISIS in attacks on Jabhat al-Nusra in Raqqa. On January 24, 2014, the battalion’s Kuwaiti backer, Jabhat al-Asala wal-Tanmiya, issued an official statement ending support for its factions. The remaining members joined ISIS. |

| Second Corps | The Second Corps was more of a coordinating body than a unified entity. |

| 11th Division – Free Syrian Army | The division was dissolved at the end of 2013. |

| Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi Brigade | This brigade joined the Raqqa Revolutionaries Brigade, then separated from it, and later joined the Unity and Liberation Front. Its leader was arrested for allegedly collaborating with the regime. The brigade was eventually dissolved. |

| Jihad fi Sabil Allah Brigade | The brigade fought against both the regime and ISIS and allied with the YPG in the Battle of Ayn al-Arab. In 2014, it restructured itself as Ahrar al-Raqqa Brigade and joined SDF in 2016, continuing its operations within their ranks to this day. |

| Owais al-Qorni Brigade | The brigade was dissolved in early 2014 by ISIS, which absorbed its members. |

| Ahfad al-Rasul Brigades | After ISIS targeted its base in August 2013, the brigade withdrew from Raqqa. |

| Muntasir Billah Brigade | The brigade joined the Raqqa Liberation Front and also became part of the 11th Division. |

| I’sar al-Shamal Brigade | ISIS eliminated the brigade at the start of 2014. |

| Al-Wihda wa al-Tahrir al-Islamiya Front in Raqqa | The faction’s leader was accused of handing over Father Paolo to ISIS. The front was dissolved on November 30, 2013, and its fighters joined ISIS. |

Table 10: The fate of military factions in Raqqa after ISIS took control of the city in early 2014.

Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently: The Last Voices

All public forms of civil activism ceased when ISIS imposed full control over Raqqa. The organization restructured the Raqqa Local Council after ousting its leader. Dissenting voices were silenced, and the residents of the city were forced to comply with ISIS-style sharia law. Those who disobeyed faced severe consequences, including arrest, flogging, other forms of torture, and even execution.

In these terribly difficult conditions, the campaign Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently was launched by a group of local activists working in complete secrecy. This initiative emerged in April 2014, at a time when media coverage was almost non-existent and information about the situation inside the city was scarce. The campaign’s mission was to confront the drastic strictures ISIS was imposing on the community, and to break Raqqa’s isolation from the outside world.

The campaign set out several key goals: to document the violations committed daily by ISIS, including public executions, forced disappearances, the conscription of children, and the imposition of draconian laws. The team also sought to build international solidarity for the victims.

The group faced many challenges. Its members didn’t even know each other’s identities. In a 2016 interview with the BBC, founding member Hussam Issa explained that this was a precautionary measure, in case one was captured by ISIS and tortured to give up the identities of the others. He added that just two weeks after the campaign’s launch, ISIS threatened through a Friday sermon to arrest and kill anyone involved with the group. Immediately after the sermon, ISIS arrested hundreds of civilians who were following the campaign’s Facebook page.[27]

An ISIS-authored document stored in the IPM archive shows that the organization confiscated a house belonging to one of the campaign’s co-founders, and used it thereafter as a military base. The document is addressed to the governor of Raqqa, and it describes the homeowner as an “apostate and agent of the international Coalition,” a charge that ISIS habitually directed against civil activists and citizen journalists. The document states that several collaborators of the homeowner have been arrested.

The Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently campaign avoided the usual means of communication, relying instead on secret networks to smuggle photos and videos to the outside world. Activists kept on the move between houses, and many had to flee the city.

But ISIS reached them even in exile. Key activists Ibrahim Abdul Kader and Fares Hammadi were assassinated in Urfa, Turkey, in September 2015. ISIS claimed responsibility for the murders in a video posted on its official channels, accusing the two of “conspiring with the crusaders against the Islamic State.”

At this great cost, Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently prevented total silence falling over the city during ISIS rule. It became a vital source of news about conditions in the city and then about the effects of the Global Coalition’s war against ISIS in 2017. When no other journalists could enter the area, the campaign provided evidence of the bombings and casualties.

Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently continues its work to this day. Its archive contains a great deal of information about Raqqa during its darkest days, preserving the stories of victims, survivors, and civil activists, while its website provides news on the current situation in the city and surrounding region.

The activists of this campaign and many others worked in the most difficult of conditions for the good of the people of Raqqa. Their courageous and inspiring work – protesting injustice, providing services, organizing the community – kept the values of the Syrian Revolution alive even while ISIS sought to drown them in blood.

- Ali al-Babinsi was born in Raqqa in 1996. A student at the Ibn Khaldoun trade school, he helped found the Raqqa Students Coordination Committee. ↑

- “Does the fall of al-Raqqa constitute a turning point in the Syrian Revolution?” The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, March 13, 2013, link. ↑

- Ahmad Alloush, or Abu Issa, was a merchant in Raqqa before the Syrian Revolution. ↑

- Ahmad al-Alloush – Abu Issa: Syrian Memory archive, link. ↑

- “Does the fall of al-Raqqa constitute a turning point in the Syrian Revolution?,” the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, March 13, 2013, link. ↑

- The 93rd Brigade was located in the Ayn Issa area of northern Raqqa province. It remained under the Assad regime’s control until it was captured by ISIS in July 2014. ↑

- The 17th Division was located in northern Raqqa province. It remained under the Assad regime’s control until it was captured by ISIS in July 2014. ↑

- The data in table 2 were gathered from the Syrian Memory archive and other publicly available sources. ↑

- The interview is kept in the IPM archive. ↑

- Born in 1973, Abu Luqman had formerly been imprisoned by the Assad regime in Saydnaya Prison after he founded a Jihadist cell in Tabqa, near Raqqa. ↑

- Muhammad al-Najjar, “ISIS, the Key Player on the Syrian Scene,” aljazeera.net, October 9, 2013, link. ↑

- Liwa Ahfad al-Rasoul was formed in Tal Abyad on October 20, 2012 under the leadership of Major Muhammad al-Awwad, who had defected from the Syrian Army. The militia was subdivided into a number of brigades, and it fought in the battles to liberate the provinces of Raqqa and Hasakah. In December 2012, it joined the Jabhat Tahrir al-Raqqa (Raqqa Liberation Front) alliance, and participated in liberating Raqqa city. Al-Awwad was killed in February 2013 and was succeeded by Ujail Karim al-Ujail, who was in turn assassinated in May 2013. ↑

- “ISIS Captures Ahfad al-Rasoul’s Bases,” the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, August 14, 2013. A copy of the report is kept at the Syrian Memory archive, link. ↑

- Tareq Ahmad, “Raqqa at the Mercy of ISIS,” al-Modon digital newspaper, September 30, 2013, link. ↑

- The data in table 5 were gathered from the Syrian Memory archive and other publicly available sources. ↑

- The IPM has gathered data given in the testimonies of the families of the disappeared and cross-checked them against publicly available information. It is worth noting that the list of names is not exhaustive and only includes a portion of the people who were forcibly disappeared. ↑

- “Kidnapped by ISIS: Failure to Uncover the Fate of Syria’s Missing,” Human Rights Watch, February 20, 2020, link. ↑

- “How Did Raqqa Fall to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria?,” Souria Hikaya (Syria Untold), January 8, 2014, link. ↑

- In Syria and elsewhere in the region, tents are often erected following a person’s death so that visitors can present their condolences to the relatives of the deceased. ↑

- Milia Eidmouni, “The Syrian Woman and Creating Change 2,” Souriya Hikaya (Syria Untold), May 27, 2016, link. ↑

- Because the Islamic calendar is based on lunar cycles, Ramadan falls nine or ten days earlier each year as compared to the Gregorian calendar. ↑

- The activist was interviewed by the ISIS Prisons Museum in 2024. They prefer to remain anonymous. ↑

- A report on the “Free Raqqa Youth Assembly” published on May 3, 2013, on the website “Syria Untold.” ↑

- A video report published in May 2013 on YouTube, covering the civil organizations operating in Raqqa. ↑

- The “Raqqa Coordination Committee” was linked to the “Local Coordination Committees of Syria” (LCCSY), an umbrella formally established on April 22, 2011. The LCCSY connected local committees organizing the revolutionary movement in various Syrian provinces. It grew to encompass around 70 local committees. ↑

- The State Organization, aka Daesh, Part Two: The Formation of Discourse and Practice: a book published by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in 2018 ↑

- An interview with Abdul Aziz Al-Hamza published by BBC Arabic in 2016 ↑