The Shaitat Massacre

Documenting the Events and Reshaping the Narrative

By: Sasha Al-Alou and Ayman Allow

Introduction

Since 2011, Syria has witnessed systematic violence committed by multiple actors. International humanitarian law has been violated again and again. Violence has been exacerbated by the complexity and longevity of the conflict, the involvement of many parties – each with competing interests – and the central government’s major role in practicing or sponsoring violence.

The massacre ISIS committed against the Shaitat clan[1] in Deir ez-Zor province in August 2014 was one of the most serious of the many massacres committed throughout the country. The documented civilian casualties exceeded 558 within a few weeks. The number later increased by at least 90. This makes it the second-worst massacre in Syria in terms of numbers (the worst was the 2013 sarin gas massacre committed by the Assad regime in the Ghouta suburbs of Damascus) and the worst committed by ISIS in Syria.

The crime shows the characteristics of a genocidal act committed with deliberate intention; an order was issued, then it was carried out against the tribe within a specific time.

The uniqueness of the Shaitat massacre is determined by its specific circumstances, yet it emerges from a larger context of violence in Deir ez-Zor in particular, and in Syria in general. ISIS arrived suddenly on the scene in Deir ez-Zor early in 2014, and immediately clashed with the ideologically diverse Syrian opposition factions. Fierce battles raged throughout the province for more than six months, but eventually ISIS came out on top.

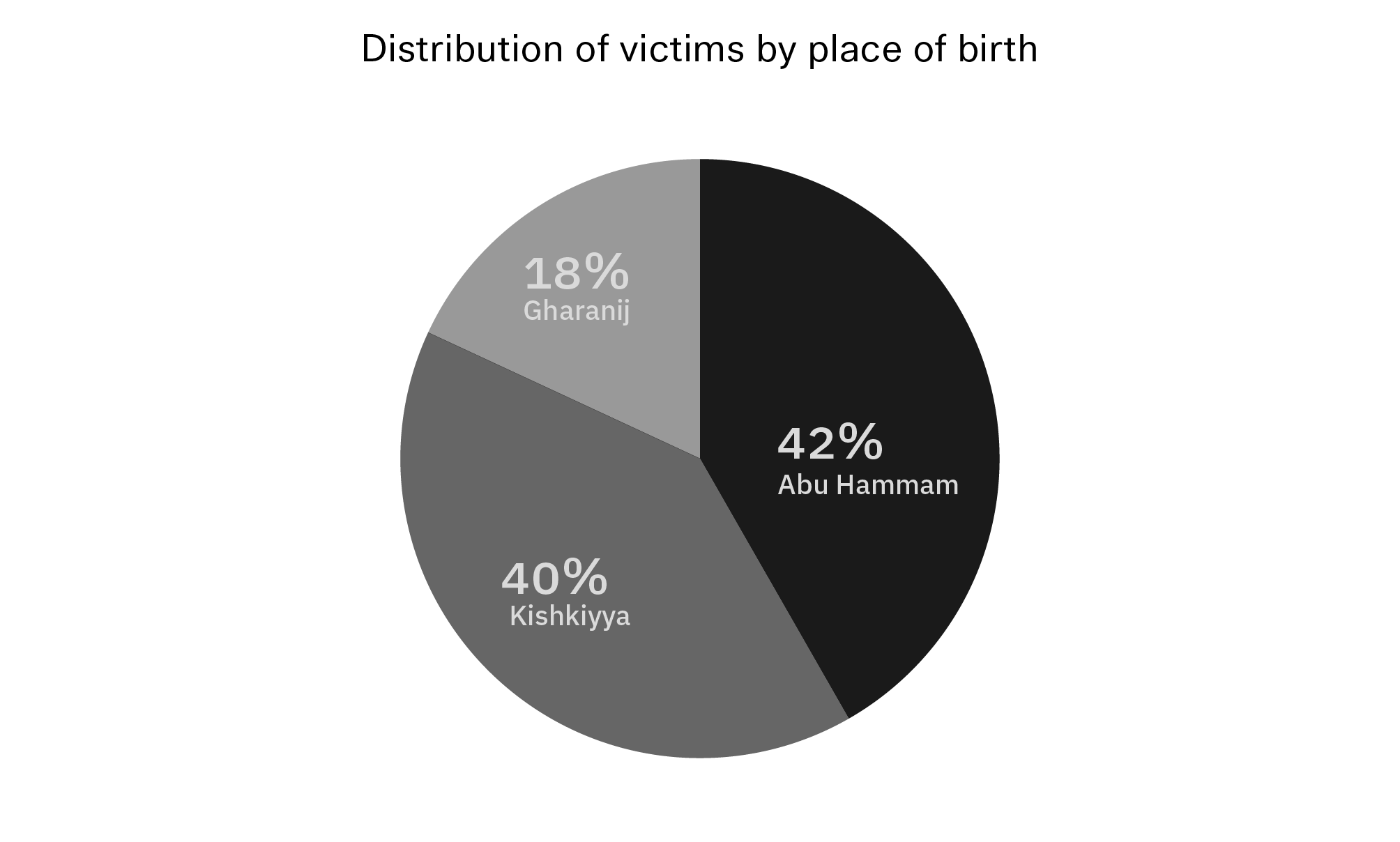

Brigades formed by the Shaitat clan were among the first to fight against ISIS. The areas where the Shaitat lived – Abu Hamam, Kishkiyya, and Gharanij – were the last parts of the province to fall under ISIS control. ISIS concluded the fighting with a series of massacres that had a long-lasting impact on the families of the victims, the entire clan, and the collective Syrian memory.

Ten years after the massacre, and despite worthy efforts, some aspects related to documentation and narrative remain problematic. The massacre has not been systematically documented or studied to the depth it demands. Insufficient attention has been paid to the direct cause of the events, to the context before and after, to the details of the events, or to establishing a clear timeline of the massacres supported by relevant documents and testimonies. The number of casualties requires further research and clarification, as different sources provide varying estimates.

In this context, the research presented here aims to document the events and to reshape the narrative of what happened.

First, it reviews the political and military context of Deir ez-Zor province when it slipped Assad-regime control, as well as the role of the Shaitat clan in the armed conflict.

Next, it covers the ISIS subjugation of the province in general and the Shaitat areas in particular, and the initial agreement that established ISIS control.

Following this, it investigates the events following the breaching of the agreement on July 30, 2014, including a 12-day battle that precipitated, in one way or another, the massacres. Each day of the battle is documented in detail, especially as the massacre, in effect, started during the battle.

The study then seeks to reshape the narrative of the incident by reviewing the timeline and details of the massacre, including mass killings, arbitrary detentions, forced displacement, looting, and the destruction of homes. It also examines attempts by local dignitaries to negotiate an end to the killing and displacement.

Finally, it examines the period after the return of displaced people to their homes, the punitive measures that led to more killing, and the discoveries of mass graves. The study provides an initial survey of the graves discovered by residents from late 2014 until 2020. It analyzes data and numbers provided by the Shaitat Victims’ Families’ Association, which conducted a 2020 survey to determine the number of casualties. Despite some gaps in its coverage, that survey remains the most comprehensive count of Shaitat casualties.

The research relies on primary and secondary data sources, including interviews with relatives of the victims and the missing, former detainees, former fighters, and tribal elders. The ISIS Prisons Museum (IPM) has conducted interviews with many individuals from diverse groups connected to the events. These include the following.

- Families of the victims. Interviews were filmed with 27 relatives of casualties and missing people; 21 were filmed between January 1 and May 30, 2021, and the rest were filmed between April 1 and June 20, 2024. The interviews were filmed in the Shaitat towns of eastern Deir ez-Zor. The interviewees were chosen carefully to represent, as much as possible, the geographic areas of Abu Hamam, Kishkiyya, and Gharanij. The majority of the interviewees are women from the victims’ families.

- Former detainees. Interviews were filmed with 26 former detainees who were held in different ISIS prisons during and after the massacre; 10 were filmed between January 1 and May 30, 2021, and the rest were filmed between April 1 and June 20, 2024. The interviews were filmed in the Shaitat towns of eastern Deir ez-Zor. The subjects were again chosen to represent, as much as possible, the geographic areas of Abu Hamam, Kishkiyya, and Gharanij.

- Former fighters. Interviews were filmed with 27 former fighters; 17 were filmed between January 1 and May 30, 2021. The subjects were a sample of Shaitat fighters who were involved in the battle against ISIS, during which the massacre began. The interviews were filmed in the Shaitat towns of eastern Deir ez-Zor, and the subjects were chosen to represent the areas of Abu Hamam, Kishkiyya, and Gharanij; 10 interviews were conducted by phone or in the field between April 1 and June 20, 2024. The subjects included former Shaitat fighters who had fought in the battle against ISIS.

- Clan chiefs and elders. Interviews were filmed with six Shaitat clan elders who were involved in the negotiations with ISIS during and after the massacre; two interviews were filmed between January 1 and May 30, 2021, and the other four were conducted between April 1 and June 20, 2024. The interviews were filmed in the Shaitat towns in eastern Deir ez-Zor. The subjects were chosen to represent, as much as possible, the areas of Abu Hamam, Kishkiyya, and Gharanij.

- Activists and journalists. Interviews were conducted with 10 activists and journalists from the Shaitat tribe who witnessed and covered the battles and witnessed the massacre. The interviewees are also relatives of the victims. Six of the interviews were conducted between January 1 and May 30 2021, and the remaining interviews were conducted between April 1 and June 20, 2024. All were conducted in the Shaitat settlements in the eastern countryside of Deir ez-Zor.

The research presented in this study also makes use of the following sources:

- Documents. The study uses more than 150 documents related to the massacre, including ISIS correspondence, circulars, and orders, texts of agreements imposed by ISIS in the area, photos and video footage of the massacre obtained from various sources – some shared by ISIS at the time and others captured by activists or other civilians – as well documents that were leaked or found in buildings abandoned by ISIS after its defeat in the area.

- The Shaitat Victims’ Families’ Association. The IPM relied on this association as a source of data on the victims and their numbers. The IPM viewed the association’s documented data from January 1, 2014 until the date of the last documented victim, August 15, 2021. The total number of dead is 814. The data were reviewed and then analyzed with multiple levels. The IPM also worked with the association in surveying the locations of the discovered mass graves until 2020.

- ISIS official social channels. During the writing of this study, the team reviewed the video and text content of ISIS social channels and accounts for the time of the massacre to collect more footage and data on the massacre and the battle and to understand the nature of ISIS media discourse at the time. The research team also conducted a long interview with a former ISIS security agent in the Shaitat area, who was released by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in exchange for a sum of money and on the condition that he stays in his village. The interview was conducted on June 15, 2024.

- The media. Local, Arab, and global media and news agencies were important secondary sources for understanding what happened in some events and in checking the timeline and dates of the battles fought to control the villages, towns, and cities of Deir ez-Zor.

- Papers, studies, and human rights reports. Research papers and human rights reports published by local or Western organizations were important secondary sources for the study. They included documentation of the massacre, study of the ISIS movement in Syria at the time, and the political and military context of the developments in Deir ez-Zor.

All of the interviews were conducted with the interviewees’ informed consent after the aims of the research had been explained to them. The interviews and documents are cataloged and kept in the IPM archive. The names of most sources have been anonymized in the study at the sources’ requests due to the security conditions in the area, in which ISIS cells remain active.

The Rise of ISIS in Deir ez-Zor

In 2014, ISIS expanded to control areas in Raqqa, Hasakah, eastern Aleppo province, and Idlib. This development disrupted the political and military calculations of the various local, regional, and international players and quickly reshaped the map of the military conflict in Syria, especially in Deir ez-Zor.

Origins and Early Battles

The original nucleus of ISIS in Deir ez-Zor lay within Jabhat al-Nusra, which had entered the province in early 2012. To start with, individual fighters and small groups fought in the province under the radar; however, by mid-2012, Jabhat al-Nusra had declared its existence, and quickly became an important player among the armed groups in Deir ez-Zor and in Syria more widely.[2]

The first ISIS fighters appeared in Deir ez-Zor after the ‘Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant’ was announced on April 9, 2013.[3] The announcement caused a split in Jabhat al-Nusra, which had originally been conceived as a Syrian branch of the Iraq-based ‘Islamic State’. Abu Muhammad al-Jowlani, Jabhat al-Nusra’s leader, rejected the decision to merge his group with the new entity, led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Some Jabhat al-Nusra fighters remained loyal to Jowlani, while others joined ISIS. The disagreement between the two groups remained merely ideological-organizational to start with, and did not escalate to a military confrontation as it did in other regions of Syria. Al-Baghdadi’s supporters gathered in villages in the east of the province, primarily in Khasham and Jadid Akidat, where they set up bases.[4]

A complicated array of militias operated in Deir ez-Zor. The factions of the Free Syrian Army had been founded by defectors from the Assad-regime army, as well as by civilians who took up arms. Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra were primarily Syrian Salafi-Jihadi militias with transnational connections. The Assad regime’s forces, meanwhile, still controlled parts of Deir ez-Zor City and strategic military locations in the countryside, such as the Deir ez-Zor air base – though they had been expelled early on from most of the Deir ez-Zor countryside.

ISIS first clashed in Deir ez-Zor with the Ahfad al-Rasoul (Descendants of the Prophet) brigades, a coalition of local armed groups supported by the staff committee of the Free Syrian Army, led by Maher al-Nuaimi, a defected officer from the Assad regime’s army. The battles began in Raqqa and quickly spread to Deir ez-Zor. ISIS accused Ahfad al-Rasoul groups of “receiving Western support to fight Islamist groups,” and in mid-September 2013 attacked their bases, managing to capture most of their weapons and detain a number of their leaders and fighters.[5] ISIS continued to pursue members of Ahfad al-Rasoul until the end of October 2013. Its victories over the group allowed it to accumulate more weaponry, which in turn strengthened it militarily in its operations against Assad forces in the province, especially at the Deir ez-Zor air base.[6] Eventually, Ahfad al-Rasoul was disbanded. It became known in ISIS propaganda as Ahfad Iblis (Descendants of Satan). Later on, some former commanders of Ahfad al-Rasoul, such as Abu Seif al-Shaiti and Saddam al-Jamal, pledged allegiance to ISIS and became active players in the takeover of the province and the Shaitat issue.[7]

After Ahfad al-Rasoul, ISIS clashed with Ahrar al-Sham and its allies. Clashes broke out intermittently in the areas of Syria where both groups were present. The first spark was on December 2, 2013 in the Deir ez-Zor countryside.[8] This fight had complex dimensions. In addition to the ideological differences between the two Jihadi groups and the struggle for control and influence, the fight reflected tribal divisions in the area. Both groups tried to attract leaders from the powerful tribes, and this led to social division. For example, the most prominent ISIS commanders in the battle were Amir al-Rafdan, who had defected from Jabhat al-Nusra,[9] and Kamal al-Raja, also known as Abu al-Muntasser al-Bariha, after his birthplace of Bariha village.[10] On the other hand, Abu Ishaq, the leader of Liwa al-Ahwaz, who was also from Bariha, fought against ISIS alongside Ahrar al-Sham, even though he belonged to the same tribe (the Bekayyir branch of the Akidat tribe) as al-Rafdan and al-Raja.

Jabhat al-Nusra remained neutral for around a month at the peak of the fighting between ISIS and Ahrar al-Sham. The fighting depleted Ahrar al-Sham’s military capabilities. Al-Nusra’s neutrality, which provoked all the armed groups in the area, remained in effect until February 2014,[11] when ISIS attacked its bases in the oil-rich town of Shadadi and Tal Hamis in Hasakah. At the same time, ISIS launched an attack led by Amir al-Rafdan on the oil and gas fields of Koniko and Jafra held by Jabhat al-Nusra, capturing them on February 2, 2014.[12] Jabhat al-Nusra fought hard for the fields. This was the first time that it had engaged in the fight against ISIS, which led many to believe that wealth-producing resources were Jabhat al-Nusra’s main concern.

Recognizing the increasing danger posed by ISIS, other militias joined Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham in the fight. ISIS had already attacked most of them while it was laying siege to the Deir ez-Zor air base in mid-January 2014, and had captured heavy weapons sent from the Aleppo countryside to help in the battle to liberate the air base.[13] Consequently, a number of militias formed an alliance to confront ISIS. The alliance included Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, Liwa al-Ahwaz/Bariha, Liwa Mouta/Shahil, Bashair al-Nasr/Ashara, the Shaitat Brigades, Liwa Jafar al-Tayyar, armed groups from Gharanij/Shaitat, Free Syrian Army groups that worked under the Mohasan military council, and individuals who volunteered to fight against ISIS.

In early February 2014, the alliance fought against ISIS in the countryside, recapturing many areas, including oil fields. It also blew up the house of the ISIS governor and commander in charge of the ISIS offensive, Amir al-Rafdan. He was chased with the remaining ISIS fighters to southern Hasakah.[14] These battles were the first time that the Shaitat brigades had clashed with ISIS.

After fierce battles that continued for days, the alliance succeeded in expelling ISIS from most of Deir ez-Zor on February 11–12, 2014, and chased its remaining fighters out of the villages of Khabour toward the southern countryside of Hasakah.[15] ISIS retained one position in the area of the salt mines in Tabanni village in Deir ez-Zor’s western countryside. The position proved to be hard to capture for geographic and military reasons.[16] After February 12, the battles moved to Markada in Hasakah’s southern countryside, and continued raging there for over two months. Hundreds from both sides were killed and wounded. Around 80 of the dead were from Shahil, the main stronghold of Jabhat al-Nusra in Deir ez-Zor at the time. Dozens from other militias and villages in Deir ez-Zor were also killed. The battles continued until mid-April 2014. Both sides used heavy weapons. Jabhat al-Nusra brought reinforcements from Aleppo, Idlib, and Homs. The armed groups used revenue from most of the oil fields in Deir ez-Zor to fund and arm their fighters.[17]

A week after ISIS withdrew to southern Hasakah, it started sending car bombs to areas of Deir ez-Zor’s countryside, most notably one in Shahil that killed dozens.[18] Meanwhile, Jabhat al-Nusra and other militias dedicated their efforts to chasing fighters who were suspected of being loyal to ISIS or collaborating with it. Jabhat al-Nusra began taking these steps in early 2013, when it accused a number of people in leadership positions of conspiring against the group and working either for ISIS or for the West. The most prominent name among those under suspicion was Saddam al-Jamal, a former field commander of the Free Syrian Army’s joint staff committee of the eastern region. He disappeared in Abu Kamal in mid-2013 after pressure from Jabhat al-Nusra, which blew up his house and assassinated his brother. At the end of the year, he appeared in a video pledging allegiance to ISIS. He later appeared in the battles of Markada, where he joined Amir al-Rafdan and the defeated ISIS fighters.[19]

After pledging allegiance to ISIS, al-Jamal was appointed as security officer of the Furat province in Iraq. He was also appointed as a commander during the Markada battles. He was in charge of planning a surprise attack on his hometown of Bukamal, launched on April 11, 2014. ISIS named the operation the “Liberating the Captives Raid.” The attack targeted the headquarters of Jabhat al-Nusra’s sharia committee in the city, killing those inside.[20]

The opposition and Islamist militias did not expect the attack on Abu Kamal because ISIS had been weakened after its previous defeat. The attack caused a shock, but it was absorbed within two days. A decisive counteroffensive was then launched. ISIS fighters were surrounded and defeated, with approximately 150 of them dead and wounded, including Nadir al-Rakhita, the second brother of Saddam al-Jamal. The main militias who participated in the battle were: Jabhat al-Nusra; Ahrar al-Sham; Liwa Omar al-Mukhtar; the Shaitat brigades; the Free Syrian Army brigades of western Bukamal; and Bashaer al-Nasr.

After the battle, ISIS was completely expelled from Bukamal. ISIS fighters withdrew and took up positions in the Syrian desert within the T2 oil pumping station (a station that pumps crude oil from Iraq and the oil fields in Deir ez-Zor toward the T3 station near Palmyra). The area, known as al-Kum, is 85 kilometers south of Bukamal.[21]

The withdrawal from Deir ez-Zor and the failed attack on Bukamal were the most significant setback for ISIS since it was founded on April 9, 2013. ISIS lost control of the Qa’im border crossing with Iraq and most of the oil fields. ISIS members longed for revenge. The defeat in Deir ez-Zor limited their movement and geographic connection to Iraq. It isolated them in Raqqa and Aleppo’s eastern countryside. It also depleted their military and human resources, with hundreds killed, wounded, or captured.

ISIS Advances through the Province

The battle in Markada continued for approximately two months until mid-April 2014, when ISIS defeated the alliance led by Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, and the Free Syrian Army brigades – including the Shaitat brigades – and took control of the area.

ISIS capitalized on the revival of military morale after Markada to recapture Deir ez-Zor. It brought in enormous military reinforcements from Aleppo, Raqqa, and Iraq, and it devised a plan – engineered by Omar al-Shishani – to assault the province from five axes on three fronts simultaneously.

First, ISIS attacked the province’s northern countryside from two axes in the southern Hasakah countryside – to the east and west of the Khabur River. Second, it attacked the western countryside from two axes – the Jazira line starting from Raqqa, and the Shamiyya line starting from the town of Maadan. Third, it launched an attack from the direction of the Syrian desert. This assault was led by Abu Ayman al-Iraqi. Several foreign and local leaders led the other assaults, most notably Omar Al-Shishani.[22]

Map 2: ISIS Attack Axes on Deir ez-Zor Countryside

ISIS launched its fiercest attack from the south of Hasakah province toward Sawar in the north of Deir ez-Zor province. Here, it engaged in “bone-breaking” battles against the opposition militias that left over 150 men of the militias dead and wounded in a short time, and even more ISIS fighters.[23] Nevertheless, ISIS took control of the town on April 16, 2014.[24] After that, it attacked the east of the province while launching another attack from Raqqa toward the west. The Euphrates divides the area into two; the western bank is called Shamiyya, while the eastern side is called Jazira. ISIS was able to surround and capture most areas in Shamiyya without much resistance, except for some sporadic battles with Ahrar al-Sham in Madan and Tabanni.[25]

At the same time, ISIS launched an attack on western Deir ez-Zor from the Syrian desert/Damascus road. It clashed with Jabhat al-Nusra in Kabajeb village, forcing it to withdraw. ISIS also fought and defeated Ahrar al-Sham in Joula. The two sides reached an agreement guaranteeing the safe withdrawal of Ahrar al-Sham fighters, but ISIS reneged on it, and killed approximately 51 men. ISIS then completed its offensive on the Jazira part of Deir ez-Zor’s western countryside, fighting on different fronts until it took full control on May 10, 2014.[26] After that, intermittent fighting continued in certain areas. ISIS was eventually able to capture these too, and established full control in early June 2014.[27]

The fall of most of Deir ez-Zor’s western countryside had a direct effect on the military scene in the rest of the province. ISIS approached Deir ez-Zor city and laid partial siege to its neighborhoods, especially after it managed to block the roads leading to the Siyasiyya bridge and other river crossings. These were the main connections between the countryside and the city. As a result, the Free Syrian Army and Jabhat al-Nusra brigades in the city found themselves squeezed between ISIS and the Assad-regime forces. The siege and the fighting caused great suffering for civilians. It is estimated that more than 100,000 fled during that period.[28]

Meanwhile, ISIS was fighting Jabhat al-Nusra and the Free Syrian Army in the eastern countryside. The heaviest fighting was on the Jazira side of the Euphrates, an area rich in oil and gas resources. Both Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS benefited from cooperation with powerful tribes. Jabhat al-Nusra set up a stronghold in Shahil, and forged an alliance with most of the al-Boujamil clan of the Akidat tribe. ISIS had previously established strongholds in the villages of Jadid Akidat and Bariha, and forged an alliance with most of the Bekayyir clan of the Akidat tribe.[29]

The ISIS offensive on this front continued after the capture of Sawar on April 16, 2014. It targeted Jadid Akidat, where battles continued for around a month, from mid-April to mid-May. Hundreds were killed and wounded on both sides. There were around 30 casualties in the Shaitat brigades, and dozens in other militias.[30] As the clashes expanded, there were initiatives to stop the fighting, especially between the two Jihadi groups fighting in Deir ez-Zor, ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra. The most important was an initiative called for by al-Qaeda’s leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri. There were also initiatives made by local tribes. All these attempts failed, and fighting continued to rage.[31]

On May 9, 2014, during the battles around Jadid Akidat, ISIS managed to capture the Koniko gas field and several nearby oil fields. At the same time, the fighting spread to the edges of Khasham.[32] ISIS finally captured Jadid Akidat in mid-May 2014.[33] After that, other villages fell one after the other. ISIS captured Jadid Bakkara, Dahla, Sabha, and Zir. In Sabha and Zir, ISIS was able to capitalize on tribal disputes. It attracted some military commanders, chief among them Ahmad Obeid al-Daham, also known as Abu Dujana al-Zir, commander of the military sector in the north of Deir ez-Zor province.[34] Now, the ISIS strategy had brought it to the edges of Basira, which connects the eastern countryside to the city of Deir ez-Zor.

Amid this increasing threat, the anti-ISIS militias gathered in the eastern countryside under a unified military command called the Mujahideen Shura Council. The formation of the council was announced on May 25, 2014, and included: Jabhat al-Nusra; Jaish al-Islam; Ahrar al-Sham; Jaish Mouta al-Islami; Bayareq Shaitat; Jabhat al-Asala wa al-Tanmiya; Harakat al-Jihad wa al-Bina;[35] and others. The new alliance fought ISIS in the eastern countryside in late May 2014. It also intermittently targeted positions in the western and northern countryside and was able to recapture some villages and towns.[36]

Despite the fierce resistance, ISIS continued to put pressure on the eastern countryside. Basira became the next line of defense after Jadid Akidat. The fighting here reached its peak in late May,[37] and ended in early June 2014, when ISIS took control.[38] ISIS then targeted villages controlled by Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham, such as Tabiyya Jazira. ISIS deployed reinforcements from the Libyan al-Battar Battalion, forcing its opponents to withdraw around June 9, 2014. Before that, ISIS had managed to neutralize Khasham and the surrounding area after an agreement with some of the militias there.[39] It established full control on June 10, 2014.[40] But ISIS reneged on the agreement it had made with the militias. It carried out summary executions and, on June 23, 2014, it forcibly displaced the residents of Khasham and Tabiyya – about 30,000 civilians.[41] Tens of thousands were fleeing, and the local councils in the area at the time declared most of the eastern and western countryside of Deir ez-Zor as a disaster area.

After this advance and the fall of Basira, ISIS reached the outskirts of Shahil, Jabhat al-Nusra’s main stronghold in Deir ez-Zor. ISIS wished to capture the town in order to cut off the supply route from Bukamal. It had momentum, and was further boosted on June 10, 2014 by the news of the Iraqi Army’s collapse and the ISIS capture of most of Mosul.[42]

ISIS benefited from the momentum and high morale. Reinforcements arrived from Iraq, strengthening the organization in Deir ez-Zor. While continuing to fight in the Jazira part of Deir ez-Zor’s eastern countryside, ISIS used different tactics in the Shamiyya part. Here, it worked hard to win over some of the local militias, and received pledges of allegiance both in secret and in public. The militias were generally given three options: to pledge allegiance, to fight, or to leave the area. The militias in the villages around Deir ez-Zor air base in particular were hard-pressed as they fought on two fronts simultaneously, against the Assad regime’s forces as well as ISIS. Regime forces continued to bomb militia positions in Mari’yya and al-Buomar. ISIS gave the armed groups there the options of pledging allegiance to ISIS, disbanding, or withdrawing. Most commanders chose to withdraw.

On the other hand, ISIS was able to strike a secret agreement with a limited group in the town of Muhasan that the town would be handed to ISIS but some militia would be permitted to remain in their positions near the air base.[43] ISIS took control of Muhasan and Boulil without a fight on June 20, 2014,[44] and executed a number of Free Syrian Army officers and commanders who rejected the agreement.[45] The agreement paved the way for the fall of many villages and towns on this front.

As well as the agreements in the countryside, ISIS managed to force allegiance from some militias based in the city, after it had besieged them. Some of these militias now transformed into ISIS cells. Other militias withdrew from their positions in the city, among them the Shaitat militias, which withdrew on June 15, 2014. On June 20, 2014, they also withdrew from their positions near Deir ez-Zor air base, after being attacked by ISIS cells in Muhasan. They returned to take up positions in the Shaitat villages. This defense had become urgent since ISIS was laying siege to Shahil and edging closer to the Shaitat villages.[46] By the end of June 2014, a new phase had started in which ISIS captured the rest of the province through negotiations and forced pledges of allegiance.

The First ISIS–Shaitat Agreement

On June 26, 2014, as news spread of negotiations brokered by the local tribes between ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra for the handover of Shahil, there were rumors too that the Shaitat brigades might hand over their areas. But Shaitat fighters quickly released a video statement denying the rumors, stressing that they would not pledge allegiance to ISIS.

Shaitat fighters were deployed on June 28, 2014 to areas around Shahil town.[47] They met Jabhat al-Nusra’s leaders at the Omar oil field to devise a combat plan and to allocate positions for the fight against ISIS.[48] According to the plan, the Shaitat fighters’ role was to protect Bukamal, given that intelligence indicated that the Jabhat al-Nusra commander in Bukamal, Abu Yousuf al-Masri, intended to hand it over to ISIS. The Shaitat brigades moved toward Bukamal via Mayadin, in order to boost the morale of the militias on that front. They planned an attack on Qouriyya, near Mayadin. The local commander Mahmoud al-Matar was based at Qouriyya, and he had pledged allegiance to ISIS.

The Shaitat brigades advanced on Qouriyya, but were stopped by an ambush. They were forced to return to Mayadin before continuing to Bukamal. Here, they ran into another ambush because the Jabhat al-Nusra commander there, Abu Yousuf al-Masri, had pledged allegiance to ISIS.[49] The two sides fought for hours. Eventually, the Shaitat forces were forced to withdraw to their villages.[50]

On June 29, 2014, the world awoke to the news that ISIS had declared itself ‘the Islamic caliphate,’ with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as caliph. ISIS released a video showing its official spokesman, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, and some military commanders watching the demolition of a section of the border between Iraq and Syria.[51]

On July 1, 2014, ISIS seized control of Bukamal.[52] The town is strategically placed on the Iraq–Syria border. Only a few pockets of resistance remained in the countryside: Jabhat al-Nusra in Shahil; Bashair al-Nasr in Ashara; and Bayareq al-Shaitat in the Shaitat villages. There was no other option left to these militias than to join the negotiations that ISIS had started in Shahil in late June.

ISIS negotiated with the Jabhat al-Nusra commanders in Shahil from the position of a victor. The terms it dictated were: the town and both heavy and light weapons were to be handed over. Fighters and residents would declare their ‘repentance.’ The residents would leave their homes for 10 days, but could return after that, once ISIS had secured the area.[53] Those who declared allegiance to ISIS would have their weapons returned.

When the terms became clear, Jabhat al-Nusra decided to withdraw its fighters, commanders, and heavy weapons during the night, in coordination with other groups, including Bashair al-Nasr and the Shaitat brigades. Some Shaitat fighters were involved specifically in the plan to withdraw the heavy weapons.

Jabhat al-Nusra withdrew into the desert with its heavy weapons on June 1 and 2, 2014, accompanied by fighters from Liwa Omar al-Mukhtar, Bashair al-Nasr, Ahrar al-Sham, the Shaitat brigades, and others. They then moved in two directions. Fighters from Ahrar al-Sham, Jabhat al-Asala wa al-Tanmiya, Liwa Omar al-Mukhtar, the Shaitat brigades, and Bashair al-Nasr headed to the Qalamoun region in central Syria. Jabhat al-Nusra fighters, meanwhile, headed to southern Syria,[54] where they joined up with groups in Daraa and Quneitra.[55]

In a video statement dated July 3, 2014, the militias remaining in Shahil, along with local dignitaries, declared their allegiance to ISIS and their total break with its enemies.[56] ISIS then occupied Shahil and displaced its residents – approximately 30,000 people – for 10 days, in accordance with the agreement.[57]

The handover of Shahil marked the end of Jabhat al-Nusra’s presence in Deir ez-Zor province. ISIS took control of Mayadin too (also on July 3, 2014) once Jabhat al-Nusra fighters had left. In Ashara and the nearby villages, some militias withdrew, while others – along with some local dignitaries and tribal chiefs – pledged allegiance to ISIS. Qouriya town avoided a battle when some of the fighters and dignitaries there – influenced by the ISIS commander Mahmoud Matar – released a video in which they pledged allegiance to ISIS.[58] (The Omar oil field fell at the same time as Qouriya.)

It is worth noting that the militias and local dignitaries did not pledge allegiance because they endorsed the ISIS ideology. They did so, rather, as a pragmatic response to the military reality that ISIS had imposed on the region. They joined after being effectively defeated. ISIS demanded public, filmed pledges of allegiance as an admission of this defeat. But even that submission did not save many. ISIS executed and imprisoned its former opponents in Mayadin, Bukamal, Qouriya, Ashara, and other towns, targeting in particular former Jabhat al-Nusra fighters and commanders, as well as officers of the Free Syrian Army brigades.

ISIS captured village after village in the countryside without a fight. When it took Abu Hardoub village, it had reached the edge of the Shaitat areas that contain the towns of Abu Hamam, Gharanij, and Kishkiyya. On July 4, ISIS captured Biqrus, west of Mayadin, and the Tanak oil field in the Shaitat desert.[59]

ISIS picked up negotiations for the handover of the Shaitat areas on July 7, 2014. In effect, these negotiations had begun during the negotiations for Shahil. Some of the Shaitat commanders met local dignitaries and other residents to decide on a unified response regarding either resistance or withdrawal. Then the Shaitat sent a military delegation to Shaddadi to negotiate with ISIS. In a meeting brokered by local figures, the Shaitat delegation – led by Abdul Baset al-Muhammad, a commander in the Katibat al-Hamza militia – met the ISIS governor of Hasakah, a Saudi national called Abu Jabal.[60] The negotiations at that stage were general and did not touch on specifics. However, ISIS leaders made clear that the Shaitat would not have a similar status to Jabhat al-Nusra in the negotiations.

When detailed negotiations for the handover of the Shaitat areas began, ISIS divided the talks by village and militia. It conducted separate negotiations with the militias of Abu Hamam and Kishkiyya (Katibat al-Hamza). At the negotiations in Abu Hamam, ISIS was represented by Abu Saif al-Shaiti. Negotiations were held in the Laiz neighborhood of Gharanij with the town’s militias (Liwa Ibn al-Qayyim and Katibat Ahfad Aysha) and local dignitaries.

The demands of the Shaitat were: that ISIS would not set up military bases in the Shaitat towns; that ISIS would provide work opportunities for the youth in the oil fields of the Shaitat desert; and that a local would be put in charge of the area.

The terms presented by ISIS, on the other hand, were: that the Shaitat’s weapons would be handed over under supervision, and Shaitat commanders would declare their repentance – those who did so would be spared, no matter how many ISIS fighters they had killed, but they would be kept under house arrest; that those who chose to leave would be permitted to do so; and, finally, that the Shaitat towns would come under the full control of ISIS. It would raise ISIS flags and be patrolled by ISIS fighters.[61]

The Shaitat militias had no choice but to accept the terms. An agreement was reached on July 8, 2014. It began to be implemented between July 9 and 12, 2014, when the Shaitat started handing over weapons in the Tanak oil field. In most cases, however, old weapons and 4×4 cars were handed over. Many light and medium weapons, such as 23-mm anti-tank guns and 57-mm artillery, were hidden instead.

ISIS was not happy with either the quantity or type of weapons that were handed over. ISIS had fought these militias for more than six months, so knew very well that they possessed heavier weapons. In this context, news about threats to some of the militia commanders began to circulate. This and other matters caused them to leave the three Shaitat towns. With ISIS in control, and local issues seemingly in the hands of local dignitaries, the military commanders considered their task complete. Most left for Turkey or for areas in Aleppo province controlled by the Free Syrian Army between July 12 and 20, 2014. They moved immediately after ISIS declared full control of the Shaitat areas on July 12, 2014. ISIS had given its former opponents a grace period until July 17 to complete their ‘repentance.’[62]

On July 14, 2014, two days after the Shaitat had handed over their weapons, ISIS entered the areas controlled by the opposition militias in Deir ez-Zor city without a fight.[63] After Jabhat al-Nusra’s withdrawal and the fall of the countryside to ISIS, the opposition militias had no other option but to come to terms. Some pledged allegiance to ISIS, while those who refused were ejected and headed to Aleppo and Idlib provinces. At that point, ISIS had control over the entire province of Deir ez-Zor except for the Assad regime’s remaining positions, which comprised two neighborhoods in the city and the military air base in the countryside.

ISIS now changed the name of the province to Wilayat al-Khair (Province of Goodness). It later delineated new administrative borders for the province, after announcing the creation of Wilayat al-Furat (Province of the Euphrates) in Iraq, which included the Syrian town of Bukamal.

The battles that ended in ISIS controlling more than 95 percent of Deir ez-Zor province left a huge number of civilian and military casualties. Human rights monitors estimate that a total 7,000 people, civilians and fighters, died in less than six months of fighting between ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra. The figure covers all of Syria, without breaking down the specific numbers for Deir ez-Zor, which was the main stage of battle.[64] As well as the dead, hundreds of thousands were displaced by the ISIS takeover, with the total number estimated to be over 350,000. Some moved to nearby provinces or further afield in Syria, while others sought refuge in Turkey and other countries.[65]

The Municipality Incident: The Catalyst of the Massacre

Amid a widespread sense of demoralization in Deir ez-Zor province after the ISIS takeover, there was at first a cautious calm in the three Shaitat towns. However, almost immediately, ISIS violated the agreement it had reached with the Shaitat. Before a week had passed, the organization set up a military base in Kishkiyya. Then it set up a checkpoint on the main road and began harassing people there with regard to their beards, dress, or smoking habits. And it repressed former fighters in the opposition militias.[66]

Many Shaitat men who had fought with Jabhat al-Nusra were detained and tortured – part of a wider purge of former Jabhat al-Nusra fighters.[67] Others were forced by increasingly visible ISIS security agents to once again declare their repentance, and once again hand over one Kalashnikov and eight magazines per man. The men had no choice but to comply if they wished to avoid prosecution in the future. The same measures were applied to anybody who had formerly worked with the opposition militias in any way, and all former media workers.[68]

The Shaitat understood these violations of the agreement as a punishment imposed by the victor on the vanquished. They had no choice but to adapt.

The gravest violation occurred on July 30, 2014, when an ISIS patrol raided a house in Abu Hamam in order to arrest a man from the al-Nahhab family. The eight-man ISIS patrol came in a 4×4 car. They included foreigners (a Belgian and a Moroccan) and locals, three of whom were men of the Shaitat tribe. According to witness testimonies, these local ISIS members bore a grudge against the man whose house was raided. They used their attachment to ISIS to exact their revenge.

The patrol headed to the al-Nahhab family home in Abu Hamam, intending to arrest a number of people there on account of a report filed by a family that had secretly pledged allegiance to ISIS. In particular, they wanted to arrest 40-year-old Hamdan Hamid al-Alyan, who was back home on vacation from his job in Kuwait. When al-Alyan refused to cooperate, the ISIS patrol shot him dead, then started to leave. But as they were going, a neighbor – Muhammad al-Nasser al-Faraj, 22 years old – came out to see what was happening. Hearing shooting next door, he had brought a personal weapon with him. He was arrested, and summarily executed. Then his corpse was mutilated in the market area of Abu Hamam.[69]

The incident shocked the Shaitat. Within hours, people gathered to protest. An improvised militia was rapidly put together by civilians and former fighters – around 50 men – in Abu Hamam.[70] The militia set out immediately and attacked an ISIS military vehicle on the town’s main road. The vehicle was carrying two ISIS members. One was a local commander named Akla al-Burjes; he was killed on the spot. The other was released.[71]

Next, the militia headed to the military base that ISIS had set up in Kishkiyya in violation of the agreement. The ISIS base was located in the town’s former municipality building. Shaitat fighters clashed with the ISIS fighters in the base, killing two (a local and a Belgian immigrant) and capturing four others (three locals and a Moroccan).[72] The captives included the ISIS sharia officer responsible for the Shaitat areas, a man known as Abu Juleibib.[73] A few hours later, relatives of one of the murdered Shaitat men killed the Moroccan and one of the local ISIS captives. The remaining two ISIS members, one of them the ISIS sharia officer, were handed into the custody of a local dignitary.[74]

News of this attack quickly reached the ISIS leadership. The closest ISIS position to Kishkiyya was in the Tanak oil field. The same day, ISIS arrested 26 Shaitat civilians who had been employed at the Tanak oil field according to the agreement. These civilians knew nothing about the incident in Kishkiyya.[75]

An atmosphere of tense apprehension covered the Shaitat areas on the evening of July 30, 2014, as news of the incident spread. It soon became known as the ‘Municipality Incident’. In an attempt to defuse the situation, meetings were held between local dignitaries and the hastily formed Shaitat militia. The militia had rapidly increased in size to around 100 men at that point, most in Abu Hamam. They divided into groups manning three fronts (the desert, Abu Hardoub, and the river) to ward off potential ISIS attacks.

Some claim that certain men joined the new militia out of personal interest, often connected to the oil trade. Nevertheless, the main reason most of the men joined was their outraged tribal identity. The men were provoked by the killing and mutilation of their kinsmen. The sense of solidarity with the tribe was strong in the Shaitat community.

The militia carried light weapons (Kalashnikovs, PK machine guns, RPGs, and sniper rifles) in addition to some medium weapons (anti-tank guns and Shilka) that had been hidden rather than handed over to ISIS at the time of the agreement.[76] But despite their possession of these weapons, the power imbalance between the militia and ISIS was enormous. The Shaitat’s military leadership had left the area, all their heavy weapons and most of their light weapons had been handed over, and there was an ammunition shortage.

It appeared to the Shaitat that ISIS had limited its response in the first days to detaining the oil employees. Unbeknownst to them, however, some ISIS sharia officers had actually taken further steps. The most prominent among these officers was Abu Abdullah al-Kuwaiti, who issued a notorious fatwa that day describing the entire Shaitat tribe as “violators of the agreement and mutineers against the rule of sharia” as represented by ISIS. The fatwa classified the tribe as “a group rebelling with force,” that is, a group that refused to submit to the rulings of ‘the sharia,’ and one that did so with force, that is, with weapons and from defensive positions. Therefore, the fatwa ruled, the Shaitat in general were: “An apostate group that must be declared as such, and must be fought as the disbelievers are fought, by the consensus of the scholars, even if they submit to the ruling of sharia and do not reject it. It is not permitted to make pacts or truces with them, nor peace. Those of them detained must not be released or exchanged for money or men. Their slaughtered animals must not be eaten. It is not permitted to marry their women or to enslave them. It is permissible to kill those of them who are detained. It is permissible to kill those fleeing and those wounded. They must be fought, even if they did not attack us first.”[77]

Even though no official ISIS document carries the text of the fatwa – ISIS fighters were usually informed of them by word of mouth – its implementation is documented in official correspondence sent by the ISIS leadership in Wilayat al-Khair (Deir ez-Zor) to the provincial sharia officer, Abu Farouq al-Tunisi. A copy of the correspondence was published by the Daily Mail. The British newspaper reported that it had been leaked by former ISIS members. The correspondence comprised two short lines: “To brother Abu al-Farouq al-Tunisi… Please abide fully by the fatwa of the scholar Abu Abdullah al-Kuwaiti in the matter of the Shaitat apostates, point by point. It is for the sake of Allah, and may Allah reward you my honorable brother.” The document is dated Shawwal 3, 1435 hijri, which corresponds to July 30, 2014. It bears the seal of Wilayat al-Khair and the signature of the sender.[78] As the date of the document shows, the fatwa was delivered and the order to carry it out was given within hours of the Municipality Incident.

A copy of the correspondence sent by the leadership of the Islamic State in Wilayat al-Khayr (Deir ez-Zor)

to Abu Farouk al-Tunisi, the sharia official in the Wilayat, bearing the text of the fatwa

This provided an ideological/sharia justification for the abuses that were to come, and served to mobilize ISIS fighters. The text of the fatwa would be translated into actions on the ground, point by point, as required by the implementation order, and would spark a 12-day battle.

Detailing the developments of each day of the battle contributes to our understanding of how events unfolded, and the context of the massacre against the Shaitat tribe.

From July 30 on, ISIS propaganda referred to the tribe as “the Shaitat apostates.”The following is a chronological rundown of the days of the battle that followed.

Day One, July 31, 2014

ISIS launched its first attempt to storm the Shaitat areas at dawn. It started on the edges of Abu Hamam because this town was closer to its forces based in Abu Hardoub, and because most of the Shaitat fighters were concentrated in the town. It was more difficult to attack Kishkiyya first in any case, as ISIS fighters risked being surrounded by forces from Gharanij and Abu Hamam. The ISIS leadership in the area thought that the battle was going to be easy, especially since heavy weapons had been confiscated from the Shaitat, most light weapons had been handed over, and most Shaitat commanders had left for other areas.

Contrary to ISIS expectations, however, its first incursion failed. ISIS used light and medium machine guns and mortar shells[79] and it relied on local militia that had only recently pledged allegiance. On the other hand, the Shaitat fighters quickly moved from defense to offense, especially after receiving reinforcements from other Shaitat areas. By evening, they had managed to advance with help from local residents, taking full control of Abu Hardoub. There were fierce clashes as ISIS shelled the village, setting the local mosque on fire.[80] By the end of the first day, ISIS had retreated to al-Jarzi village, with around 14 of its fighters dead or wounded. Four Shaitat fighters had been killed, and others were wounded, in addition to dead and wounded among the fighters of Abu Hardoub.

ISIS shared on its social channels, meanwhile, photographs of the civilian oil employees who had been detained the previous day. They appeared handcuffed in some of the photographs. Others showed them being tortured. All the photos were captioned with the following words: “Hyenas of al-Sharqiyya… in the grasp of the caliphate’s lions.” The photos heightened tensions in the Shaitat areas and increased fears about the fate of the captives.[81]

Day Two, August 1, 2014

On the second day, the two sides fought fiercely on the edges of al-Jarzi town. The Shaitat fighters advanced, capturing al-Jarzi al-Sharqi near Abu Hardoub. During this advance, a group composed of residents from the nearby Sweidan village attacked ISIS fighters, burned their main base in the village, and forced them to retreat from there and the neighboring village of al-Jarzi al-Gharbi.[82] Fighters on both sides were killed.

The Shaitat fighters continued their advance, and this encouraged many in the nearby areas. Militias in Ashara composed of former Free Syrian Army fighters attacked the main ISIS checkpoint in the town, expelling the fighters.[83]

As the fighting expanded to more locations, many civilians fled. Both sides suffered casualties, meanwhile, and tried to reorganize their fighters. The Shaitat fighters reorganized their militias, with Abdul Baset al-Muhammad taking military leadership. A former commander in the Hamza brigade, al-Muhammad fought many battles against Assad-regime forces before joining the fight against ISIS in Deir ez-Zor. Unlike other commanders, he hadn’t left for Turkey or northern Syria. He had field experience and was well known to the Shaitat.[84]

Abdul Baset al-Muhammad taking the Shaitat fighters leader (Local Sources)

Also on this day, dignitaries decided to release the two remaining ISIS captives without negotiations. The freed captives headed to the Tanak oil field.

Day Three, August 2, 2014

Surprising military developments occurred at dawn. ISIS fighters made a partial retreat from the Jazira/eastern-countryside front (the area stretching from the Shaitat towns to Baghouz on the Iraqi border) but kept on patrolling there. They also withdrew from some oil fields in the Shaitat desert, gathering at the Tanak oil field, which became a battle command center. This strange retreat had multiple aims, most notably to mass ISIS fighters in the battle zone and to secure the largest oil field. This was especially important as ISIS had captured the area only recently and had not yet established strict control. Another goal was to open up a route for those Shaitat who wished to retreat. ISIS did not want to lay full siege to the area for fear that the entire tribe might rise against it. At the time, it was trying to limit the battle to the militias in Abu Hamam.

Battles continued simultaneously in the al-Jarzi desert, Abu Hardoub, and Sweidan, causing many people to flee their homes. ISIS launched a fierce attack on the Abu Hamam desert and Shaitat fighters rushed from the fronts in nearby villages to repel this attack. ISIS also set up artillery in the Dweir area, opposite Abu Hamam, and began shelling the town. ISIS fighters advanced toward Ashara, which had risen the previous day, and recaptured it.

During the day, news spread that ISIS had killed the oil employees at the Tanak oil field, but nobody had yet seen any proof.

Day Four, August 3, 2014

ISIS brought a military column from al-Qa’im in Iraq into Deir ez-Zor’s eastern countryside;[85] 4×4 cars carrying fighters and weapons moved through the villages and towns of the area in an intimidatory display of power. The column contained heavy weapons such as Gvozdika artillery, tanks, as well as the American Hummers that ISIS had captured in Mosul.

As the battles continued, meanwhile, ISIS fighters recaptured Sweidan Jazira. The Shaitat fighters retreated to the edges of Abu Hardoub and al-Jarzli amid fierce clashes on the Abu Hamam desert front.[86]

The most significant event of the day was that improvised civilian groups (former oil traders, people who worked at the burners or in transportation, and others) took control of some of the oil fields in the Shaitat desert. Because ISIS had redeployed its fighters from these fields to the Tanak oil field, the civilians thought that it had lost the area and would not return. They sought to take advantage of the situation, but some would ultimately meet their end by the oil installations.[87]

Day Five, August 4, 2014

After bringing in reinforcements and intensifying the shelling, ISIS managed to recapture al-Jarzi al-Sharqi and al-Jarzi al-Gharbi.[88] The Shaitat fighters retreated to Abu Hamam. Most of the clashes occurred on the Sanour front. After capturing al-Jarzi, ISIS fighters arrested and summarily executed civilians as they were moving about the village. Some residents of Sweidan Jazira who had been displaced by fighting in the previous days, meanwhile, returned to their homes now that ISIS had regained control.[89]

On this day, rumors spread that the Shaitat militias that had retreated to Qalamoun when ISIS captured Deir ez-Zor might return to support their relatives, and might bring heavy weapons with them. This would remain a false hope. The rumor may have started because the Shaitat and other militias that had withdrawn from Deir ez-Zor had formed a new alliance in Qalamoun – Jaish Osoud al-Sharqiyya – which declared that its main goal was to fight against ISIS.[90]

Day Six, August 5, 2014

ISIS brought further reinforcements from Shaddadi in Hasakah, and attacked fiercely.[91] New clashes occurred on the edges of al-Jarzi al-Sharqi. However, the fiercest battles were in Abu Hamam. Here, ISIS fighters tried to infiltrate via the Euphrates from Abu Hardoub, but the Shaitat were able to repel them. Heavy shelling caused many more people to flee the Shaitat areas, especially Abu Hamam.

The important role of ISIS foreign fighters became clear in these battles. The organization fielded fighters from Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Chechnya, and elsewhere, as well as the Libyan al-Battar militia, which was notorious for its brutality. It appears ISIS chose to deploy the Libyan militia as a result of its local forces’ failure over the previous days.[92] ISIS also waged a propaganda battle to spread fear about the strength of the al-Battar militia.

This day marked the first deployment of ISIS suicide bombers in the battle. Also on this day, ISIS published photographs of the Shaitat civilians it had executed in al-Jarzi village the day before. Their heads had been cut off and displayed on the main road.[93]

ISIS also prevented the displaced residents of Abu Hardoub and al-Jarzi al-Sharqi from returning to their homes, because some fighters from those villages had joined the Shaitat offensive. The displaced were only allowed to return in mid-September 2014,[94] on the condition that each village provided ISIS with a specific amount of weapons.

Meanwhile, the Assad regime’s air force bombed an ISIS position in al-Jarzi. Regime media and loyalist social media channels suggested that the strike was carried out in support of the Shaitat fighters. In reality, it was part of a series of attacks launched by the regime against ISIS since the local militias had been defeated. At the time, ISIS was preparing to attack regime positions at the Deir ez-Zor and Tabqa air bases. The airstrikes therefore aimed to weaken ISIS throughout the province and the eastern region as a whole, not just in the Shaitat areas. A review of regime airstrikes on this day shows that they targeted ISIS positions in multiple towns and villages far from the Shaitat areas, in Zir, Qouriyya, Basira, Bukamal, and elsewhere.[95]

A day earlier, regime forces had targeted Deir ez-Zor’s western countryside with heavy airstrikes and artillery shelling, causing the displacement of 5,000 residents, mostly women and children, from the villages of Ayyash al-Kharita and Hawayij Ziyab toward the areas of al-Zighir Shamiyya and Shamitiyya, near the Euphrates. The bombing also targeted ISIS positions in Tayyana, causing the death of civilians, including children.[96]

The regime would continue to attempt to win over the tribes of Deir ez-Zor in general and the Shaitat in particular – to make them a first line of defense for its belated fight against ISIS.[97]

Day Seven, August 6, 2014

Early in the day, lines of communication were opened between the two sides. These were brokered by local Shaitat dignitaries, notably Abu Seif al-Shaiti and Jaafar al-Khalifa, who had pledged allegiance to ISIS and were biased in the organization’s favor. ISIS demands at the time were: that the names of those who had participated in the fighting were to be given to ISIS; that the civilians were to leave their homes for some days while ISIS combed and secured the Shaitat areas; and that residents would guarantee that no support would be given to the fighters, and that no new volunteers would join them.

The negotiations failed. Shaitat dignitaries and fighters rejected the ISIS demands, particularly concerning the displacement of civilians and the handing over of fighters’ names. There were around 200 Shaitat fighters at the time, 100 of them active on the front lines, and the rest guarding the rear or their own neighborhoods.[98]

More civilians chose to leave their homes, especially after heavy shelling targeted Abu Hamam from the desert and the Euphrates.

Day Eight, August 7, 2014

ISIS released photographs purporting to show the execution of the 26 civilian oil employees arrested on July 30, 2014. The 26 were shot dead or had had their throats cut in an open space in the desert.[99] The precise location of the massacre was discovered six years later.[100]

The photographs provoked a lot of anger and motivated more people, especially the relatives of the murdered oil workers, to join the militias in Abu Hamam.

ISIS continued its indiscriminate shelling of Abu Hamam. It hit battle positions, houses, and schools, causing civilian casualties and a new wave of displacement from Abu Hamam to the villages around Bukamal or on the other side of the Euphrates/Shamiyya.[101] Under cover of the shelling, the ISIS forces advanced. They included foreign fighters marching on foot. They were spearheaded by the Libyan al-Battar militia, but the Libyans were ambushed, and suffered around 20 casualties. Around 15 ISIS fighters were captured, including minors.[102]

A few hours later, ISIS launched another attack, using Hummers and armored vehicles. This assault broke the Shaitat’s first line of defense. As the Shaitat fighters retreated and ISIS advanced, efforts were made to mobilize support for the fighters in Abu Hamam. The mosques of the Shaitat areas and social media accounts broadcast appeals for help. In response, a group of volunteers headed from Gharanij toward Abu Hamam.[103] The group was shelled by ISIS midway. This made some turn back, but others reached Abu Hamam. This increased the number of Shaitat fighters in Abu Hamam to approximately 250. Together, they set up a second defensive line.

During the day’s battles, the Shaitat fighters used 57-mm artillery for the first time, but it did not make much difference, due to a shortage of ammunition.[104]

Day Nine, August 8, 2014

The clashes continued amid heavy shelling of Abu Hamam. By this point, around 70 percent of residents had fled, and the remaining 30 percent were sheltering on the outskirts of the town, away from the front line.

During the day, increasing numbers of people fled from other Shaitat areas toward Bukamal. ISIS patrols arrested some of them in al-Bahra village. Later, it became known that ISIS had executed these people on the spot.[105] From this day on, displaced Shaitat were arrested in and around Bukamal.

The most significant event of the day was ISIS attacking multiple oil fields, including Bir al-Milh. ISIS had withdrawn from these fields on the third day of the battle. On the fourth day, groups of Shaitat civilians had moved in and taken control of them. Now, ISIS captured around 20 civilians who were operating the oil field machinery. Most managed to escape, however. For a few weeks, the fate of the detainees remained unknown. Later, ISIS released video footage showing some of them being executed near Bir al-Milh.[106]

Day Ten, August 9, 2014

The developments of the tenth day were critical. ISIS intensified its shelling and launched a new attack on Abu Hamam from two fronts. The Shaitat defenses collapsed. The fighters lost control of half the town and retreated to the Qahawi area in the town center.

The defenses collapsed for many reasons, including: the shortage of heavy weapons and of ammunition; an insufficient number of fighters to cover every front or to properly rotate so that they could rest; insufficient medical supplies to treat the rapidly rising number of casualties; and the fact that fighters sometimes had to leave the battlefield to assist their fleeing families.[107]

A loss of morale had a big impact too. After 10 days of fierce fighting, no local or international body had offered significant support. Certainly, some limited support came from neighboring tribes, such as the Shaitat’s relatives in the Akidat tribe. Shafa village secretly provided weapons and ammunition, and the villages of Abu Hardoub, al-Jarzi, Sweidan, and Ashara had risen. But this was not enough to change the tide of battle. The Shaitat did not receive active, organized military support from the neighboring tribes. ISIS had been working hard to win over prominent figures in various tribes, which caused great division. Beyond that, ISIS had recently combed and purged the villages of the region. Their residents were afraid of being persecuted.

The ISIS advance and the Shaitat retreat provoked another wave of displacement from Abu Hamam. The town emptied almost completely after the fighters warned the civilians that their ammunition was running out and they might not be able to continue fighting. Fearing the battles might spread, many people left Kishkiyya and Gharanij too. Most fled to villages near Bukamal, such as Shafa, Sousa, Hajin, and Bahra.[108]

At this point, the Shaitat fighters received news of a possible ISIS attack on Gharanij, aiming to besiege the Shaitat fighters in Abu Hamam. This led them to set up checkpoints around Gharanij facing the desert and Bahra.

The first ISIS attack came in the evening, with a car bomb driven by a man bearing the nom de guerre Abu Mujahed al-Jazrawi. The car bomb blew up at a Shaitat checkpoint on the Bahra road, killing six fighters and wounding a number of civilians.[109] The chaos of the mass displacement, with the roads crowded, exacerbated the destruction of the car bomb.

Meanwhile, the Assad regime’s air force launched two airstrikes on locations around the Shaitat areas. One hit an ISIS base at Marwaniyya school. The other hit artillery pieces in Dweir. These strikes, like the previous ones, were part of a series of attacks on ISIS locations throughout Deir ez-Zor. This time, however, the Shaitat residents found leaflets in the streets shortly before the strikes. They contained words of support and encouragement to continue fighting, and were signed by the Syrian armed forces. The leaflets were dropped over many other villages and towns in Deir ez-Zor’s eastern countryside. One leaflet encouraged the various clans of the eastern countryside to rise up against ISIS. It reminded them of their history of struggle and called on their tribal solidarity.[110] Some residents think that helicopters dropped the leaflets, but the majority think the Assad regime’s informants in the area had secretly dropped them in the streets.

The leaflets had little impact on the Shaitat or the other clans of Deir ez-Zor’s eastern countryside. People knew that the regime had attacked them with various weapons over the previous years. Moreover, most of the clans in these areas were overwhelmingly opposed to the Assad regime.

Nevertheless, the leaflets, and the activities of Assad-regime agents in the area, created some confusion. A few Shaitat fighters in Abu Hamam suggested flying the Syrian flag used by the Assad regime in an attempt to receive air support. But the suggestion was rejected by the majority, who were implacably opposed to the regime; many had in the past fought against the Assad forces. For ISIS, though, the leaflets served to paint the Shaitat fighters as agents of the Assad regime.[111]

The regime did not succeed in winning over the area’s population. Neither did it influence the battle between the Shaitat fighters and ISIS.[112]

Day Eleven, August 10, 2014

In the afternoon, ISIS fighters managed to sneak behind the Shaitat fighters into Gharanij and Kiskhiyya. They set up mortar cannons and positioned snipers on the high buildings of these towns. This greatly complicated the situation. The Shaitat fighters in Abu Hamam were now surrounded on all sides, except for the River Euphrates, their only remaining retreat route.

This led to their collapse. They retreated in groups from Kishkiyya and Abu Hamam to Gharanij and the villages around Bukamal. Fighters led by Abdul Baset al-Muhammad took positions in Gharanij, but the majority sought refuge around Bukamal. There was no possibility of success, so they got rid of their weapons and hid among civilians.[113]

A delegation of Shaitat dignitaries now headed to Qa’im, just across the border in Iraq, to meet the ISIS governor and to try to set up a meeting with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in order to seek pardon for the civilians. However, after it had been made to wait, the delegation was not offered meetings with those leaders. Instead, an ISIS field commander informed the delegation that any attempts to intervene were rejected, and that the Shaitat areas would be stormed. He then told them to leave immediately.[114]

Some media outlets reported that ISIS had already re-established control over the Shaitat areas.[115] ISIS stormed schools in Shafa where displaced Shaitat civilians were sheltering. Dozens were arrested and around seven were executed. The rest were taken to prisons in Iraq, according to eyewitnesses.

Day Twelve, August 11, 2014

After the withdrawal of the Shaitat fighters, ISIS entered Kishkiyya and Abu Hamam and started searching every house. Nobody remained in the towns except imams taking refuge in their mosques, and some women, elderly people, and disabled people who had stayed to protect their homes. ISIS filmed itself summarily executing some of these people and the videos were later leaked.[116]

In the afternoon, ISIS attacked Gharanij from the desert. Three small Shaitat groups remained in the town – 40 fighters at most, who had retreated from Abu Hamam. They tried to resist, but in vain. They retreated toward Hajin after burying some weapons and throwing others into the Euphrates.[117]

A group of Gharanij dignitaries released a video and a written statement later that day. They disowned the fighters and asked for the civilians to be pardoned.[118] This had no effect. Huge numbers fled from Gharanij toward Bukamal’s villages. The town was almost completely emptied.

ISIS declared control of the Shaitat areas after 12 days of battle. Its victory did not conclude the events, however. It actually led to more bloodshed.

Approximately 23 Shaitat fighters were killed in the battles, and tens more were wounded, according to testimonies of Shaitat fighters who were present. No information is available concerning the number of ISIS casualties. (ISIS did not announce its battle losses.)

Most of the fighters left for other areas. A small group led by Abdul Baset al-Muhammad was surrounded in the desert. This made them decide to cross into the Assad regime’s areas. They continued their fight against ISIS thereafter under the banner of the Assad regime and Russia. Another group of fighters later joined the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in their US-sponsored fight against ISIS. Still others joined the Shaitat militias in the opposition brigades that fought against ISIS in Qalamoun, the Syrian desert, and elsewhere.

Massacre and Displacement: Elements of Genocide

After ISIS had taken control of their region, the displaced civilians of Shaitat were concentrated in the towns and villages of Bukamal. They were overwhelmed by fear as ISIS began targeting them with arrest campaigns during the last days of the battle, and as images and accounts of summary executions began to arrive.

On August 12, 2014, ISIS brought large numbers of fighters into the Bukamal villages, set up checkpoints and roadblocks, and pursued any Shaitat fighters who had fled to the area.

The largest proportion of the displaced civilians were concentrated in the villages and towns of Bahra, Shaafa, Sousa, Hajin and others, where they sheltered with relatives, with families who had opened their homes to them, in schools, tents, and damaged buildings, and by the sides of the roads. A smaller number of women and children were displaced to a camp in the Abu Hamam desert, where conditions were harsh.[119]

In the first two days after the fighting ended, a relative calm prevailed in the villages of Bukamal. This was short-lived, however. ISIS launched an arrest campaign on August 14, 2014. Led by the Libyan Battar Battalion and local ISIS security groups, the campaign targeted displaced civilians, particularly in Hajin and Bahra, where most were concentrated. Many civilian men, young and old, were arrested randomly. Several were summarily executed before they had reached the places of detention. They were charged with nothing other than being from the Shaitat.[120]

The campaign escalated. Places where displaced civilians had gathered – schools, tent camps, and private homes – were targeted. Many were also arrested at the checkpoints deployed by ISIS on the main roads – especially the Jaabi checkpoint between Hajin and Bahra, the Shaafa checkpoint, and the Salhiya–Shamiyya checkpoint, where Shaitat civilians trying to flee to Damascus were arrested. Those arrested either carried identity cards showing they came from Gharanij, Kishkiyya, and Abu Hamam, or they were pointed out by local ISIS informants.

According to testimonies by the relatives of victims, these arrests were often followed by summary executions. Executions occurred in various locations, including in schools repurposed by ISIS as temporary detention centers for those arrested at nearby checkpoints. For instance, at the Shaafa checkpoint, numerous Shaitat civilians, including women and children, were abducted and taken to a nearby school. Many of the men and boys were summarily executed. At other ISIS checkpoints, detainees were taken to nearby open areas for execution. ISIS patrols also raided the tents of displaced civilians, taking individual males or sometimes all male family members to locations about a kilometer away to be killed. In some cases, the victims’ bodies were left at the execution site. This forced their families, especially those who had heard the gunshots minutes after the arrest and at close range, to wait until sunset to sneak to the execution sites, retrieve the bodies of their loved ones, and secretly bury them.[121]

Such incidents, whether experienced directly by the displaced civilians or indirectly through conversation and ‘leaked videos,’ put most males in a state of apprehension. This led them to either flee these areas or go into hiding. They hid in houses, in the desert, or in farmland on both sides of the Euphrates River. They fled by side roads and using false papers. Some mothers even dressed their men up as women during raids.[122]

During the first two days of the campaign, more than 500 people from the Shaitat clan, including minors, were detained, and dozens were executed. ISIS published photos of large numbers of detainees being held in various places or being loaded into ISIS vehicles. Some were transferred to detention centers set up in empty Shaitat towns or to other areas under ISIS control in Deir ez-Zor province, such as the Omar oil field.[123]

A video leaked by an ISIS member shows prisoners from the Shaitat

tribe (a copy is preserved in the IPM archive)

The arrest campaigns continued to expand beyond the towns of Bukamal to target members of the Shaitat clan living in various ISIS-controlled areas throughout Deir ez-Zor province, such as the towns of Mayadeen, Ashara, and others. ISIS also issued orders to arrest the Shaitat at checkpoints in other Syrian provinces under its control, such as Raqqa and the countryside of Hasakah and Aleppo, where a number were arrested while trying to escape. ISIS also warned drivers heading to Damascus not to transport wanted Shaitat men carrying forged papers, threatening to burn their vehicles and kill them if they did.

The word Shaitat itself had become a serious accusation. Anyone who dealt with the tribe’s members by covering for them or harboring their wanted males was at risk of being killed. This was especially true after ISIS warned some towns – such as Shaafa – against harboring the Shaitat, threatening to kill anyone who covered for them.

ISIS detainees from the al-Shaitat tribe (Shaitat Victims’ Families’ Association)

Several incidents were reported in which civilians from other clans and towns were arrested and killed simply for hosting displaced or wanted individuals belonging to the Shaitat clan. Some of these hosts, adhering to their tribal customs, refused to hand over their Shaitat guests and clashed with ISIS members. This resistance led to their arrest or killing along with their Shaitat guests, as well as the demolition of their houses.[124] On the other hand, many families were afraid to take in those who had fled due to the potential threat that might pose.

As the raids continued, the number of detainees and missing persons increased, and the number of mass killings documented by eyewitnesses or filmed by civilians, or seen in videos leaked by ISIS members, escalated. Local human rights observatories and international news agencies estimated the number of victims to be around 700 dead and more than 1,800 missing.[125] That harsh reality forced more than 40 Shaitat elders from Kishkiyya and Abu Hamam to appeal in a video recording to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS, to stop the killing of innocent civilians.[126] The appeal fell on deaf ears and the massacre continued to escalate.

The suffering of the displaced people was compounded by the scarcity of food and medical supplies, the high temperatures during that period, and the lack or cramped nature of housing due to multiple families being forced to share small spaces. In addition, the majority of civilians experienced displacement many times, as they moved from one town to another in search of safety in a short period of time. These difficult conditions forced some of them to sneak back to their towns in desperation to retrieve belongings like blankets. They were often caught and executed, particularly after ISIS had declared the Shaitat towns a military zone.[127]

The tragedy was exacerbated by the grief and despair that gripped the families of the missing and the deceased. While the majority of families remained unaware of the fate of their loved ones, those who knew the location of their bodies buried them at night, and did so in haste and fear due to the threat of ISIS patrols. Women suppressed their screams and cries to avoid being discovered during these swift, secret burials, and families were prevented from holding mourning congregations or publicly expressing their grief.

The Shaitat women bore the greatest burden during this period. They had to search for their sons and husbands by visiting various ISIS bases, inquiring about them, and seeking any information they could, always to no avail. They also bore responsibility for securing basic daily needs, as the men were detained or hiding, fearing being arrested or killed.[128]

While arrests and raids took place in many Bukamal towns, the empty Shaitat towns became another place of massacre. ISIS converted abandoned schools and houses in Gharanij, Kishkiyyah, and Abu Hamam towns into prisons in which people transferred from other Bukamal towns were detained, tortured, or executed. Many photos and videos were leaked that showed beheaded bodies scattered on the streets. A group of these images was leaked on August 19, 2014 by civilians who had sneaked into the Maadan neighborhood in Gharanij. Other pictures were later spread by ISIS members from the neighborhoods of Abu Hamam and Kishkiyya, or from the outskirts of Badia.[129]

In those areas, ISIS seized abandoned houses and sold their contents in other towns as “spoils from the apostates.”[130] Other houses, particularly those belonging to wanted persons, were either blown up or demolished, and the destruction was filmed and broadcast by ISIS.[131]

On August 20, 2014, tribal delegations composed of notable Shaitat figures intensified their efforts to stop the massacre. They did so in response to the ongoing arrests, which now exceeded 2,000 detainees, and the violent practices, which bore the characteristics of a genocide. Several elders and sheikhs traveled to the ISIS strongholds in Deir ez-Zor province, such as Mayadin, Bukamal, Hajin, Jadid Akidat, Tayanah, and others, as well as to the Karama area in Raqqa governorate and to Mosul in Iraq.[132] On August 24, 2014, Deir ez-Zor tribal figures and sheikhs issued a video statement calling on al-Baghdadi to pardon the Shaitat clan.[133]